Library as the Center of Information

In today’s world, it is common for people of all ages to be familiar with books, magazines, newspapers, movies, and other media, they are available in libraries and stores everywhere. Many people purchase them, and become well-versed in the issues presented. However, there are many times that materials have been published that are not available in the local stores or libraries. Does this mean a researcher ignores those resources? What about resources that are no longer available for sale, does the researcher ignore those as well? College-level research demands that students expand their boundaries of information to include resources of all types and formats, and many instructors require students to use library resources.

Libraries were developed for communities of learners that shared their resources. As these groups of patrons emerged, they discovered they needed different types of materials, and libraries have four main categories, named by the type of patrons they serve. Public libraries serve members of the general public in their community, including all age groups. Materials are purchased to support their interests, and to empower them to be involved in their community. Public libraries are operated through city, county, or district governing systems, usually with tax funds.

School libraries develop programming and materials to support the curriculum at each level served by the school. An elementary school library rarely purchases materials on advanced physics, because the curriculum would probably include basic physics concepts appropriate for an elementary class. Students are encouraged to use the materials for their reading level, and teachers work with the school librarian on research projects appropriate for their classes. Many schools have teacher-librarians, that teach students about library organization, information literacy, and library tools. Many other schools have aides that focus on clerical duties, such as checking materials in/out and arranging the materials in a library. Some school libraries have been able to justify both positions for their schools, and the students are more literate as a result.

Academic libraries are similar to school libraries, developing collections and services for their patrons, but for students, staff and faculty of the college or university of which they are a part. Academic libraries often have more specialized collections, in support of the programs offered at the college/university. For example, a university with a medical program in nursing would have extensive medical materials, but a university with a full medical school for physicians would have an even more extensive medical collection. Another university that does not have any medical programs, but has an architecture program would have an extensive architectural collection in lieu of medical materials. However, any college or university that offers liberal arts, would offer a general collection to support most programs included in the “general education” courses considered important to lay the foundation for all degree programs.

Special libraries are developed for a specialized patron, such as for a business or research group. Many law firms have libraries with staff to research issues related to their cases, corporations have libraries to provide their staff with resources related to their products and services. Also, many hospitals and medical centers have libraries to provide medical information for their patients and medical staff. Many museums have libraries to provide resources to their staff for developing exhibits. Each state in the United States has a library that provides resources for their government officials, and many of these state libraries have other responsibilities as well. Each special library is unique in the type of services they provide to their patrons, and many are open only to their researchers.

a. Library Organization

While each of these types of libraries has a different focus of collection and services, they have many common organizational and administrative elements. All libraries have a system of organizing their materials, and they choose the appropriate system for their patrons and collection. The materials are labeled with a call number for the classification system, so the materials are grouped by subject area on the shelves.

Most school and public libraries classify their materials using the Dewey Decimal System, which has ten major subject divisions, and each division has ten subdivisions. An example of how the Dewey Decimal System works is below:

| 000 | Generals works, Computer Science, Information Science | ||||

| 100 | Philosophy & Psychology | ||||

| 200 | Religion | ||||

| 300 | Social Sciences | ||||

| 400 | Languages | ||||

| 500 | Pure Sciences | ||||

| 510 | Mathematics | ||||

| 520 | Astronomy | ||||

| 521 | Celestial Mechanics | ||||

| 522 | Techniques, Procedures, Apparatus, Equipment, Materials | ||||

| 523 | Specific Celestial Bodies & Phenomena | ||||

| 523.1 | Universe, Galaxies, Quasars | ||||

| 523.2 | Planetary Systems | ||||

| 523.3 | Moon | ||||

| 523.4 | Planets, Asteroids, etc. | ||||

| 523.41 | Mercury | ||||

| 523.42 | Venus | ||||

| 523.43 | Mars | ||||

| 523.44 | Asteroids (Planetoids) | ||||

| 523.45 | Jupiter | ||||

| 523.46 | Saturn | ||||

| 523.47 | Uranus | ||||

| 523.48 | Neptune | ||||

| 523.49 | Trans-Neptunian Objects | ||||

| 523.5 | Meteors, Solar Wind, Zodiacal Light | ||||

| 523.6 | Comets | ||||

| 523.7 | Sun | ||||

| 523.8 | Stars | ||||

| 523.9 | Satellites & Rings, Eclipses, Transits, Occultations | ||||

| 524 | |||||

| 525 | Earth (Astronomical Geography) | ||||

| 526 | Mathematical Geography | ||||

| 527 | Celestial Navigation | ||||

| 528 | Ephemerides | ||||

| 529 | Chronology | ||||

| 530 | Physics | ||||

| 540 | Chemistry | ||||

| 550 | Earth Sciences & Geology | ||||

| 560 | Fossils & Prehistoric Life | ||||

| 570 | Biology | ||||

| 580 | Plants (Botany) | ||||

| 590 | Animals (Zoology) | ||||

| 600 | Applied Sciences | ||||

| 700 | Arts & Recreation | ||||

| 800 | Literature | ||||

| 900 | History & Geography |

(Dewey Decimal System, DDC23 Summaries, https://www.oclc.org/content/dam/oclc/dewey/ddc23-summaries.pdf)

Many research and university libraries have extensive collections in specific disciplines, and found the Dewey Decimal System limiting the specificity that materials could be classified. As a result, most academic libraries classify their materials with the Library of Congress System which uses both letters and numbers in the call number. There are 24 main divisions, that begin with letters and most of those divisions have subdivisions with a second letter, and then numbers divide each subdivision. There are letters and number sequences that are not in use, anticipating the development of new areas of knowledge. An example of the Library of Congress system organization framework is below.

A General Works

B-BJ Philosophy, Psychology

BL-BQ Religion (General). Hinduism, Judaism, Islam, Buddhism

BR-BX Christianity, Bible

C Auxiliary Sciences of History

D-DR History (General) and History of Europe

DS-DX History of Asia, Africa, Australia, New Zealand, etc.

E-F History: America

G Geography. Maps. Anthropology. Recreation

H Social Sciences

J Political Science

K Law in General. Comparative and Uniform Law. Jurisprudence

L Education

M Music and Books on Music

N Fine Arts

P Language and Literature

Q Science

QA Mathematics

QB Astronomy

QB 1-139 General

QB 140-237 Practical & Spherical Astronomy

QB 275-343 Geodesy

QB 349-421 Theoretical Astronomy & Celestial Mechanics

QB 455-456 Astrogeology

QB 460-466 Astrophysics

QB 468-480 Non-optical Methods of Astronomy

QB 495-903 Descriptive Astronomy

QB 500.5-785 Solar System

QB 631 Earth

QB 639 Mars

QB 651 Asteroids

QB 661 Jupiter

QB 671 Saturn

QB 681 Uranus

QB 691 Neptune

QB 701 Pluto

QB 799-903 Stars

QB 980-991 Cosmogony & Cosmology

QC Physics

QD Chemistry

QE Geology

QH Natural History & Biology

QK Botany

QL Zoology

QM Human Anatomy

QP Physiology

QR Microbiology

R Medicine

S Agriculture

T Technology

U-V Military Science. Naval Science

Z Bibliography. Library Science. Information Resources

Federal Depository Library Program

Beginning in 1814 Congress began designating various universities, historical societies, and state libraries as repositories for copies of government records and documents. By the end of the 19th century, the number of depository libraries rose to more than 400. As a result, many public and academic libraries have government document collections, which use the Superintendent of Documents (SuDoc) classification system. The SuDoc system assigns call numbers based on the government agency that sponsored the project the publication is about. However, since government agencies often change names and responsibilities, the system is frequently changing divisions.

In addition, there are specialized classification systems for most subject specialties, for example hospital and medical libraries use a system developed by the National Library of Medicine. These classification systems are important tools to organize library materials by subject. However, most libraries also prefer to sort materials by format, shelving the books in one area by call number, government documents in call number order in another area, periodicals in another area by call number, etc. There are often separate sections for audio-visual media, maps, pamphlets, and other media formats.

Materials acquired for specific purposes, such as reference, archives and reserves may be kept separate from the circulating collection, but all have call numbers within their sections.

Library Organization Video

b. Library Services

Most libraries have several common services for their patrons. Reference services help library patrons use library tools and materials to locate information upon request. Circulation staff check materials in/out for patrons, and keep the collection accessible for the patrons. Cataloging staff assign call numbers and other classification information for library materials in the library catalog, and prepare them for use by the patrons. Interlibrary Loan makes arrangements with other libraries to borrow materials for their library patrons. Computer Systems maintain the library computer systems, such as the library catalog, periodical databases, and public access computers. Many academic and school libraries also provide distance library services for patrons at remote locations, such as off-campus instruction centers. Some libraries have Preservation, Restoration and Archival Storage services, to restore and care for rare and archival materials.

c. Library Tools

Libraries use several tools to maintain the organization of materials, and proper use is important to successful research. A database is an organizational resource for items that have common elements. For example, the Internet Movie Database (IMDb) has production information on most movies produced by major studios. For each movie, the producer, director, cast of characters with actors/actresses, plot summary, camera crew are included in separate fields, and the information for each movie is one record.

A library catalog is a database of the materials in the library collection, with the call number, title, author/editor, publisher name, publication date, subject headings, and other descriptive information about each item. For many decades, libraries used card catalogs, with index cards arranged alphabetically for each title, author and subject heading. With the development of computers, most libraries have an online catalog or OPAC, that also allows keyword searching. Some online library catalogs have more fields for each title, such as book reviews, author biographies, etc.

For many years, the library catalog was the only library tool for patrons to use when searching for information in a library. Originally, the library catalog was printed in large books, which were difficult to update with new titles. For each title, the author(s) names, subject headings and call numbers were printed, with six books per page in alphabetical order, and each book that was added had to be inserted in the title, author and subject sections of the printed library catalog. Libraries could not reprint the library catalog each time a new book was added, it was reprinted annually at best. Meanwhile, library patrons became dependent on librarians to locate material.

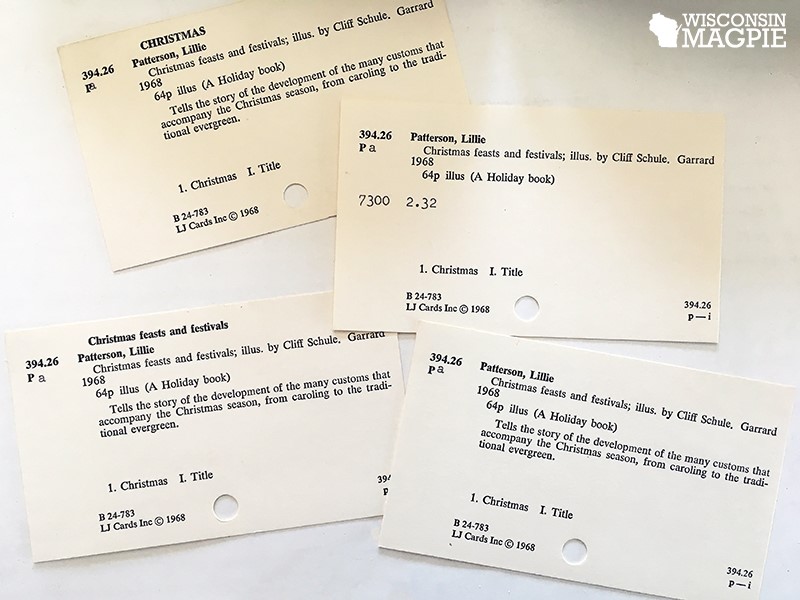

In the 1880’s, the newly founded American Library Association urged libraries to print citation, subject headings and call number for all titles on cards in cabinet drawers. The Library of Congress led the way in developing a uniform format for the catalog cards, and most libraries found this consistency helpful for patrons and library staff in locating information and maintaining the collection. Most libraries had at least three cards for each title, although all cards were the same except for the heading. One card would have the author’s name at the top, another would have the title at the top, and each title would have at least one card with a subject heading at the top. In many libraries, the author cards with the author’s name at the top were filed separately from the title cards and subject cards, and kept in separate cabinets. In these library catalogs, it was important to maintain the library catalog with staff filers that added cards as new books were added to the library. While these library catalogs were usually kept where patrons could access them easily, maintaining the card catalog was an arduous task.

In the 1980’s computers became prominent in libraries. Rather than typing each card for each title, the information could be entered in a system that formatted all cards for a title, and all cards were printed via computer. While the cards were still printed and filed, the development of this computer system laid the foundation for the OPAC, or Online Public Access Catalog. After the standard computer system was fully developed, the citation, subject headings and call number for each title were entered using MARC records. MARC was an acronym for Machine Readable Catalog records, which were compiled into the OPAC, or the Online Public Access Catalog and could be searched electronically. No longer were patrons limited to searching alphabetically for a title, subject or author, they could enter their search for any keyword, anywhere in the record and the location of that information would be provided in the call number. In addition, when a title was acquired by a library the citation, subject headings and call number were entered electronically, so less filing and other physical manipulation of data for each title was necessary.

Today, most libraries use a computerized system, and many libraries merge their collections by electronically networking their catalogs. Many libraries share cataloging information, and make their collections available between libraries. While all of this was encouraged before OPAC’s, it became much easier for libraries to collaborate using computers and Internet capabilities. Library catalogs include information on materials they have in the collection, whether in print or electronic formats. For each of the titles, the catalog includes the title, author(s)/editor(s), subject headings, and publication information. All library catalogs include the call number which denotes the location of the material in the library.

Recently, library software companies have developed Integrated Library Systems (ILS) which focus on keyword searching rather than subject searching to locate library materials. Many patrons seem to prefer this type of library catalog, although the relevance of results often declines with the vast number of results. Materials are tagged with commonly used keywords, rather than the approved and controlled list of subject headings. A list of results usually has a list of facets to limit the results by date of publication, type of publication, major concepts, geographical area, etc., and this method is often considered more use-friendly.

Periodical databases have records for articles from periodicals, which are magazines, newspapers, journals, yearbooks, and other publications that are published in regular intervals. For most articles, each record includes the author’s name, the title of the article, publication name, date, volume, issue, page numbers, subject headings and abstract. Periodical databases compile the article information with the publishers’ approval, and libraries purchase the databases. The decision about what periodicals to include in the database is made by the database developers, regardless of what any library subscribes to. A full-text electronic version of the article is often available with online databases. There are some indexes of publications that only provide citation information of publications on specific subjects, such as Web of Science. For many years, periodical indexes were published in print, with updates sent to each library that subscribed, such as the Reader’s Guide to Periodical Literature. Many researchers locating information about historical events before the 1980’s need to use print indexes to select citations, then locate the publications.

In addition, Discovery systems merge library catalogs with periodical databases, and the results can be limited to the one the library patrons have access to. However, the frustration for many is that the results include many sources that are not accessible to the library patrons. Still, patrons are able to learn of many sources they would not be aware of otherwise, but that does add to their frustrations sometimes.

ISU Library Catalog & OneSearch