Evaluating Resources: Deciding What to Use

After deciding what topic to explore and developing a search strategy, many students jump to reading and learning from the sources. However, the Internet has made so many sources available after a quick search, whether from a database or using Google, and choosing the reliable sources becomes difficult. Databases have features that you can use to narrow the results by date, and you can select a publication type, but otherwise, the researcher simply accepts the sources provided via the computer. Internet search engines, such as Google provide a list of results that is overwhelming, and researchers often choose something from the top, however naïve and gullible that may be.

While the databases and the Internet have made locating sources very quick and simple, selecting quality sources has become more challenging. There are several elements of every source that should be evaluated when determining if a source is considered “credible” and worthy of use as a source of information, based on an acronym, SCORE.

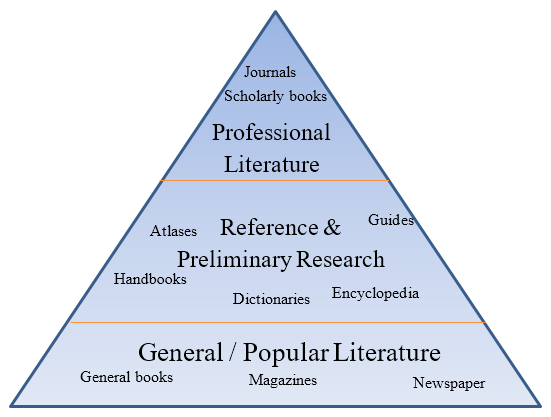

Scope is the level of depth a topic that is presented this level of depth is determined by the intended audience.

Most popular literature is developed for the general public, and those interested are not expected to have a degree or extensive experience to be able to understand the material presented. This includes magazines, newspapers, books and many websites intended for the general public.

Professional literature is developed by professionals for professionals in the same field. For example, medical professionals do research and publish their results for other medical professionals, sharing their knowledge about treatments, and other issues of the profession. Most of this professional literature is peer reviewed which means that other medical professionals have reviewed the information presented and verified the reasoning, methodology and conclusions of the research. Usually this is done with a blind review process, which means that the reviewers do not know the identity of the researcher or vice versa. This peer blind review process adds a great deal of credibility to the resulting publication, which is usually a journal article.

This professional literature is often much more in-depth than most of the general public can understand, and students beginning their research with journal articles are often overwhelmed with advanced terminology, technical and theoretical knowledge that is common knowledge to most professionals in that field. Primary research is important to understand the professional literature on a topic, to provide the background information necessary to understand the advanced information in the professional literature.

Reference materials help to bridge the information gap between professional and popular literature on a topic. Dictionaries, encyclopedia, atlases, handbooks, and other reference sources are important tools to understand the advanced concepts in professional literature. It is important for college students to recognize that these are not intended to be used as major resources in their research, but rather to help them understand the sources expected to be used in college-level research.

Currency is the factor that is often the most easily recognized as important to the credibility of a source of information. For example, when looking at information about moon exploration it would be important to know that the information about the design of the space shuttle includes the concepts learned as a result of the Challenger explosion in 1985. While currency is crucial, Internet sources often do not include the date material is posted, updated or acquired. A general guideline is that for college-level research, most sources should be no more than five (5) years old. There are topics such as those dealing with technology, that information should be less than three (3) years old. And, there are other topics, such as historical events that researchers are encouraged to use original documents. In addition, many students need more background on their topic than just the recently published sources, especially for topics dealing with cultural issues and conflicts that have brewed for several generations. In summary, the general guideline is that research sources should present information less than five (5) years old, but sources up to ten (10) years old may be used, depending on the topic. Sources that are more than ten (10) years old should be verified as to their importance and credibility.

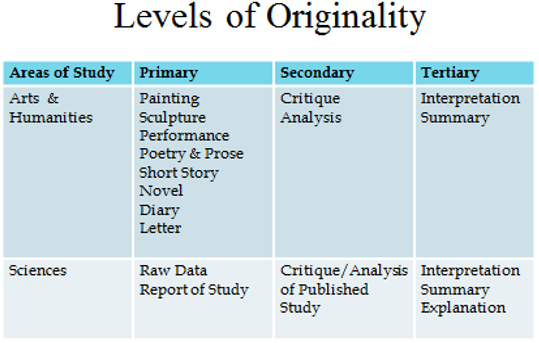

Originality level refers to the type of research that is the source of information presented in the resource. Primary sources are the result of research studies, that are described on p.9 that discusses the various types of research. These sources are written by the researcher that did the experiments, compiled the data and made the conclusions from the evidence. Most primary research studies are published in professional journals, and are recommended for most college-level research projects. Secondary sources use primary sources to compile, interpret information on a topic, or critique a creative work. These articles are published in both professional literature and general literature that are for specific interest groups. Tertiary sources are compiled from primary and secondary sources, and the information is presented more casually, as if the material is common knowledge. Most tertiary sources are websites, newspaper and magazine articles, and researchers need to verify the information in them. Often the information published in tertiary sources is not credible and is not based on research.

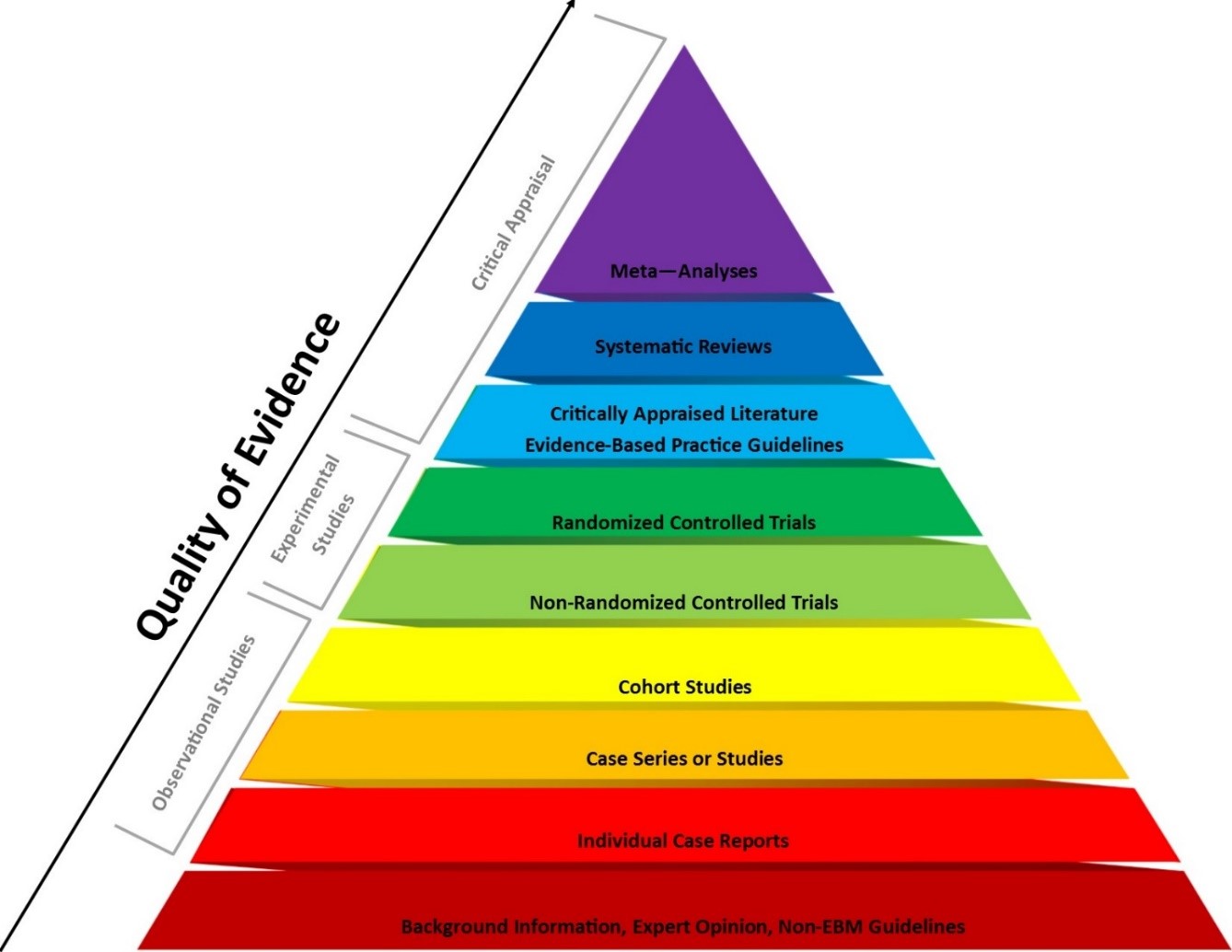

In addition, in many of the advanced sciences, there is a hierarchy of evidence. Although primary research includes original research, some types of research have stronger evidence than others. For example, in the diagram below, all the article types could be results of primary research, but a single case report may contradict the results of several case reports and randomized controlled trials that would be published as a systematic review. Recognizing the type of evidence is key when determining what evidence is stronger, and therefore more credible.

Figure 1. Evidence-Based Medicine for the College of Medicine: Resources by Levels of Evidence. Retrieved from http://libguides.cmich.edu/cmed/ebm/pyramid

Follow the progression of a research idea in this scenario. First, student is assigned a research project on fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS). There may be several articles in magazines and newspapers about the problem, these are mostly tertiary sources. Pursuit of more advanced information may lead the student to journal articles that are written by medical practitioners that express their opinion of the problem, but without a research protocol in place. Those articles would be considered expert opinion, and not be based on Evidence Based Medicine Guidelines. The student may locate several articles about individuals that are born with FAS, which are case reports. A case study or case series would compile several of those case reports and generalize many elements common to each case report. A cohort study is the result of a group with the same condition are monitored and experimental treatment may be applied to the group. The results would be compiled with statistical analysis and this statistical evidence would be even stronger. A controlled trial applies a treatment to a group that has a condition, either non-randomly selected or randomly selected. The non-random selection controls the population and may have more bias statistically, compared with the randomized controlled trial. Studies that provide results based on previous guidelines, are the next level, and systematic reviews compile results from several case studies, cohort studies and controlled trials. A meta-analysis is a type of systematic review that combines all the studies together statistically, getting a larger number of “participants” and re-calculating the results. Although the systematic review and meta-analysis articles are not the result of primary research, the compilation of previous research makes the evidence is the strongest of all. An common analogy is to consider each type of study a strand of rope, and when you combine them all, it becomes very strong and is the least biased.

Reason focuses on the purpose of the author in presenting the material. As with all media, there are many materials developed for entertainment purposes, and the public enjoys them. Of course, some of these entertaining presentations reveal issues and concerns of communities and groups around the world, but they are presented with a focus on their entertainment value, and researchers would be remiss in using them as sources for a research project. Other media presentations are developed to persuade their audience to accept or purchase an idea, product or service, and present their material with bias. Materials used as sources for college-level research should may be entertaining or persuasive, but their purpose is to inform about a topic with little or no bias. If the purpose is anything besides to inform, the source is NOT recommended for research.

Expertise is justification for accepting the author as an authority on the subject, and verification that their voice has merit. Most authors develop materials in their area of professional expertise, although there are many professionals that also publish materials on their personal interests that are not founded on research, but rather their personal experiences. While these are valid experiences, researchers need to carefully verify that authors are presenting information founded on research in their area of professional expertise. Most professional literature provide authors’ names and current positions, and these should be relevant to the topic presented. General and popular publications often require subject area specialties, although many do not require academic or professional expertise, their only standard is the author’s ability to communicate to the intended audience. Despite the standard of the publication, to be considered an “expert,” a master’s degree and several years of experience are required in most disciplines. Many publications only have the author’s name, which is helpful, but usually if the author is an expert, that information is provided. Sources with no author listed leave the researcher guessing about the author’s expertise.

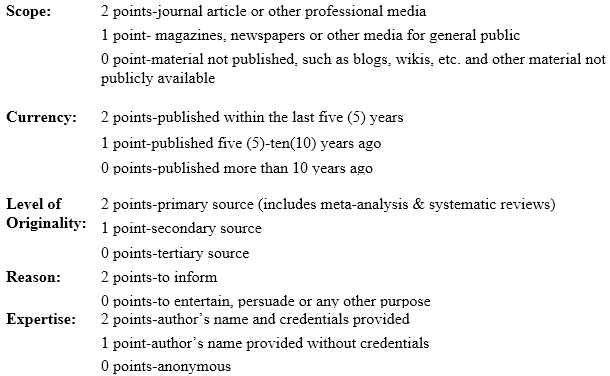

Each of these criteria should be assessed for every source considered relevant to the research topic. In most databases, it is fairly easy to note the intended audience or scope, currency and expertise of author. The originality level and reason are assessed by the researcher with a great deal of discernment. As a researcher selects sources, the rubric below can help assess each source, using the acronym SCORE, for each of the criteria: Scope, Currency, Originality, Reason and Expertise. With two (2) points for each criteria, there is a possibility of ten (10) points for each article for a credibility score. A relevance assessment combined with the credibility score should provide a thorough assessment of each source.

For most articles, simply find some white space near the citation and assess each criteria, then add up the points for each citation. This credibility score will act as a “grade” for each source. Most sources that score eight to ten points are considered credible and worth using, if relevant to the topic. Sources that score six or seven points need to be questioned as to their usefulness for the research project. There may be some value and reason to continue using them, but there may be sources that have stronger credibility scores. Sources that have a credibility score of five (5) or less have a very low credibility score, and possibly should be deselected. If a researcher has mostly sources with low credibility scores, they probably should talk to the instructor or get research assistance from a librarian.

SCORE Video