Vygotsky’s Sociocultural Theory

Autumn Salsberry

Learning Objectives

By the end of the chapter, you will be able to…

- Note at least 2 impacts Sociocultural Theory could have on learner development

- Define at least 3 key aspects of the Sociocultural Theory

- Identify how collaboration, language, and scaffolding in learning impact student development

Introduction

View this video for 5 minute introduction to Sociocultural Theory by Dr. Yu-Ling Lee.

Overview

The sociocultural theory of learning and teaching is widely recognized in fields of educational psychology and instructional technology. The focus of this theory is on the role social interaction and culture play in the development of higher-order thinking skills. Lev Vygotsky (1978), a Russian psychologist and the founder of sociocultural theory, believed that human development and learning originate in social and cultural interaction. In other words, the ways people interact with others and the culture in which they live shape their mental abilities.

Importance

Most instructional design models, such as ADDIE, take into consideration only the common learner, tying learning with concrete and measurable objectives. Recently, a strong call has been issued for a complete shift in our education and instructional design approaches. Learner-centered instruction, now, better reflect our society’s changing educational needs (Watson & Reigeluth, 2016). New methodologies, such as Universal Design for Learning, recognize that every learner is unique and strives to provide challenging and engaging curricula for diverse learners. Watson and Reigeluth (2016) mention that there are two important features of learning-centered instruction: a focus on the individual learner and a focus on effective learning practices. Sociocultural theory and related methodologies may provide a valuable contribution to this effort as they focus on a learner in their social, cultural, and historical context. They also facilitate development of critical thinking and encourage lifelong learning (Grabinger, Aplin, & Ponnappa-Brenner, 2007).

Many instructional methodologies generally do not give much consideration for learner’s funds of knowledge (existing knowledge, established relationships, or cultural richness). Garrison and Akyol (2013) explained that the use of these funds of knowledge ensures collaboration and deep communication are enhanced. Establishment of solid social presence further reflects in positive learning outcomes, increased satisfaction, and improved retention (Garrison & Akyol, 2013). Integrating sociocultural practices into learning design allows a learner’s previous knowledge, relationships, and cultural experiences to ease them into the new community (Grabinger et al., 2007).

Image description: A collage of illustrations showing various scenes – market interactions, a family in a car, a child coloring, cooking, bike riding, watching a sunset, and a teacher with a student as examples of a person’s diverse funds of knowledge.

Origins of the Learning Theory

Growing up in a middle-class Jewish family in Soviet Russia, Lev Vygotsky’s interest in psychology was shaped by the intellectual Russian environment at the beginning of the 20th century. There were significant social and political changes happening at this time (Bassett, 2024). This socio-political context is noteworthy for the influence of Soviet Russian Marxist ideas. For example, people’s material environment (cell phone, house, school, etc.) gives rise to their identity (Marx, 1845). Though Vygotsky graduated with a law degree from Moscow University, in 1925, he began a research project that focused on the psychology of art. Shortly thereafter, he pursued a career as a psychologist and worked with Alexander Luria and Alexei Leontiev. Together, they began the Vygotskian approach to psychology (Bassett, 2024).

Comparison with Piaget’s Cognitive Development

Vygotskian notion of social learning stands in contrast to some of Piaget’s more popular ideas of cognitive development. Piaget assumes that development through certain stages is mostly determined by age. This difference significantly influences learning experiences. If we believe, as Piaget did, then we will make sure that new concepts and problems are not introduced until learners are a specific age to learn that material. On the other hand, if we believe as Vygotsky did, then we will ensure that activities promote learning no matter the age. We will know that learning itself enables achievement, which in turn affects a child’s “readiness to learn a new concept” (Miller, 2011).

Image Description: Illustration comparing Piaget’s cognitive development model focusing on individual exploration and Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory emphasizing learning through social interaction.

Fundamental Tenets of Sociocultural Theory

Key Concepts

There are three fundamental concepts that define sociocultural theory: (1) social interaction plays an important role in learning, (2) language is a necessary tool in the learning process, and (3) learning occurs within the Zone of Proximal Development.

Vygotsky believed that thinking has social origins and that cognitive development cannot be understood without looking at the social context. He proposed that social interaction plays a critical role in the process of cognitive development. This is especially true for the development of higher order thinking skills. Social activity between a parent and a child or a teacher and a learner lays a foundation for how and what the child will think and do in other situations (Driscoll, 2000).

The second important notion is related to the role of language in the learning process. Vygotsky thought that social structures determine people’s working conditions and social interactions, which in turn shape their thinking, beliefs, attitudes, and perception of reality (Miller 2011). Further, human action is brought about by tools and signs, or semiotics (language, systems of counting, conventional signs, works of art, etc.). Vygotsky suggested that through the use of these tools, knowledge is facilitated such that people’s social and individual thought processes are developed. This means that children and learners do not need to reinvent already existing tools in order to be able to use them.

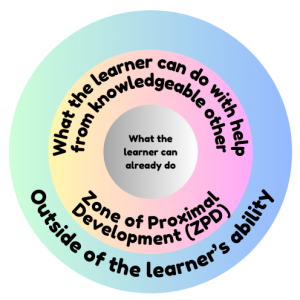

Probably the most widely adopted concept related to sociocultural theory is the concept of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD). It is learning zone between things that are simple enough for the learner to do on their own and the things that are far out of reach of the learner (Vygotsky, 1978). It is where a student learns through doing or seeing. Vygotsky strongly believed that learning should be matched with a child’s ZPD. A knowledgeable other is used to guide learners in improving their ZPD.

Image Description: A colorful diagram illustrating learner capabilities, with three concentric circles labeled: What the learner can already do, What the learner can do with help from knowledgeable other (which is the Zone of Proximal Development), and Outside of the learner’s ability.

Key Takeaways

Supporting Mechanisms

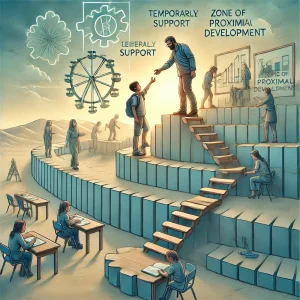

Researchers have applied the metaphor of scaffolds (the temporary platforms on which construction workers stand) to this way of teaching. Scaffolding is the temporary support that caregivers give a child to do a task. It represents the way a child’s learning is guided by offering or withdrawing support at different levels depending on the child’s individual developmental level and learning needs. Typically, both the learner and the one providing the scaffold influence each other and adjust their behavior as they collaborate.

Check your understanding for some key words below, by dragging the correct term into the blank to complete the sentence.

Image Description: An illustration depicting educational growth, featuring figures on steps labeled “support,” with students studying at desks below.

Strengths and Limitations of the Theory

Strengths

Sociocultural theory is sensitive to diversity. In contrast to many other universalist theories, sociocultural theory acknowledges both differences in individuals within a culture and differences in individuals across cultures. It recognizes that “different historical and cultural circumstances may encourage different developmental routes to any given developmental endpoint” (Miller, 2011, p. 198). This depends on the particular social or physical circumstances and tools available. Thus, focusing on the development of critical thinking, problem solving, research, and lifelong learning, helps educators meet the goal of preparing people for an ever-changing world (Grabinger et al., 2007).

Limitations

Vygotsky’s premature death was a major limitation to Sociocultural Theory because his ideas remained incomplete. Furthermore, his work was largely unknown until fairly recently due to political reasons and issues with translation. The second major limitation is associated with the vagueness of the ZPD. Individuals may have wide or narrow zones, which may be both desirable and undesirable, depending on the circumstances. Knowing how large the zone is doesn’t help educators understand the learner better (Miller, 2011). Additionally, there is little known about whether a child’s zone is comparable across different topics, with different individuals, and whether the size of the zone changes over time.

Select the correct answers in the following questions.

Instructional Design Implications

Practical Applications

An important implication of the above ideas is that the school system can easily influence the cognitive development of children. Vygotsky’s ideas suggest that student-teacher and student-peer relationships are of prime importance of facilitating new ideas, perspectives, and cognitive strategies. Furthermore, the student apprentice can be seen to be active within their learning environments, attempting to build understanding where possible. In turn, the classroom environment itself is influenced, and thus an exchange takes place between learning and the social world (Tudge & Winterhoff, 1993). In a similar way, Vygotsky has argued that natural (i.e. biological) and cultural development happen at the same time and merge to influence personality (Vygotsky, 1962).

Alternative examples of guided participation can be seen when caregivers involve infants and toddlers in everyday routines. In her research with Mayan families in Guatemala, Rogoff et al., (1993) reported mothers guiding their toddlers through the process of making tortillas. Mothers would give the toddlers small balls of dough to practice rolling and flattening. This activity contributed to the child’s cognitive development and helps them better understand their culture. As another example, consider a daycare during meal time where toddlers are seated with a caregiver and the meal is separated into larger bowls on the table where the toddlers are seated. The toddlers are able to participate in the routine by serving themselves using the serving spoons and then feed themselves using the utensils. The first few times this routine is started, the caregiver may do more serving and guiding, but eventually, through practiced participation, toddlers are able to participate more deeply, all the while learning culturally-valuable skills such as turn-taking, conversation around a meal, vocabulary and the motor skills needed to serve and eat.

Image Description: A photo of a caregiver and 3 toddlers eating at daycare with communal dishes in the center that they serve themselves from.

Strategies

Students should be given frequent opportunities to express understanding. Learning tasks can be fine-tuned by the teacher to address individual ability levels. Social interaction is key to the learning process. Therefore, the student needs to be active in the learning interaction, and in collaboration with the teacher. When large classes are inevitable, small group work should be encouraged. This is so peer-support and improved teacher interaction can be maintained. However, too much reliance on peer-support could prevent learning, so teachers must pay close attention to student-peer collaboration. Furthermore, in school, a teacher is likely the best role model.

Contexts

Sociocultural theory encourages instructional designers to apply principles of collaborative practice that go beyond social constructivism to create learning communities. The sociocultural perspective views learning taking place through interaction, negotiation, and collaboration in solving authentic problems while emphasizing learning from experience and conversations, which is more than cooperative learning. This is visible, for example, in the ideas of situated learning, cognitive apprenticeships, and third-space integration.

Brown, Collins, and Duguid (1989), who are influential authors on situated cognition, recognized that “activity and situations are integral to cognition and learning” (p. 32). By socially interacting with others in real life contexts, learning occurs on deeper levels. This implicit understanding of the world around them influences how learners understand and respond to instruction. In one study, Carraher, Carraher, and Schliemann (1985) researched Brazilian children solving mathematics problems while selling produce. While selling produce, the context and tools positively influenced a child’s ability to work through mathematics problems, use appropriate strategies, and find correct solutions. However, these children failed to solve the same problems when they were presented out of context in more common mathematical question form.

Cognitive apprenticeships, meanwhile, acknowledge the situated nature of cognition by contextualizing learning (Brown et al., 1989) through apprenticing learners to more knowledgeable others who model and scaffold implicit and explicit concepts to be learned. Lave and Wenger (1991) wrote about the work of teaching tailors in Liberia and found that new tailors developed the necessary skills by serving apprenticeships and learning from experienced tailors.

Third-space culture encourages teachers to create learning experiences that provide opportunities to build off of learners’ primary language (related to informal settings such as home and the community) and students’ secondary language (related to formal learning settings such as schools) (Soja, 1998). Studies that have examined learning experiences related to third space culture benefited learners through demonstrated gains in their understanding and use of academic language (Maniotes, 2005).

Conclusion

The dynamic relationships between culture, history, peer interactions and psychological development have been described, and the important role of language as a way to exchange ideas was discussed. One specific educational application of such ideas is through the ZPD. It emphasizes the importance of the social aspect of learning, and particularly the student-centered and collaborative nature of learning. If we believe as Vygotsky did that learning drives development and that development occurs as we learn new ideas and principles, then our instructional design will look very different than many traditional learning environments.

Students have many opportunities to experience meaningful collaborative learning in both physical and virtual settings with this theory. Different technological and online tools can assist with greater communication strategies, more realistic simulations of real-world problem scenarios, and even greater flexibility when seeking to scaffold instruction within students’ ZPD. Embracing the use of technology within collaborative learning can also foster a more equal distribution of voices as compared to in-person groupings (Deal, 2009), potentially providing greater opportunity to ensure active participation among all students. Through using technology to support the implementation of social learning theories in the classroom, students experience collaboration while refining 21st century skills.

Read the statements below and choose the correct sentence according to Sociocultural Theory.

References

Basilio, M. & Rodriguez, C. (2017). How toddlers think with their hands: social and private gestures as evidence of cognitive self-regulation in guided play with objects. Early Child Development and Care, 187(12), 12. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2016.1202944

Bassett, Jane (2024, April 1). For a progressive pedagogy: why we need Vygotsky. International Socialism. https://isj.org.uk/progressive-pedagogy-vygotsky/#:~:text=Vygotsky%20was%20born%20in%201896,communities%20were%20on%20the%20rise. Biggs, J. B., & Moore, P. J. (1993). Process of learning (3rd ed.). London: Prentice Hall.

Brown, J.S., Collins, A., Duguid, P. (1989). Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educational Researcher, 18(1). pp. 32-42

Carraher, T. N., Carraher, D. W., & Schliemann, A. D. (1985). Mathematics in the streets and in schools. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 3(1), 21–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-835x.1985.tb00951.x

Deal, A. D. (2009). Collaboration tools. Eberly Center. Carnegie Mellon University. Retrieved March 16, 2025, from https://www.cmu.edu/teaching/technology/whitepapers/

Driscoll, M. P. (2000). Psychology of learning for instruction. Allyn & Bacon.

Garrison, D. R., & Akyol, Z. (2013). The community of inquiry theoretical framework. Handbook of Distance Education, 3, 104-120.

Grabinger, S., Aplin, C., & Ponnappa-Brenner, G. (2007). Instructional design for sociocultural learning environments. W-Journal of Instructional Science and Technology, 10(1), n1.

John-Steiner, V., & Mahn, H. (1996). Sociocultural approaches to learning and development: A Vygotskian framework. Educational Psychologist, 31(3-4), 191-206.

Maniotes, L. K. (2005). The transformative power of literary third space. Doctoral dissertation, School of Education, University of Colorado, Boulder.

Maniotes, L. K. (2005). The transformative power of literary third space [Ph. D. Thesis]. University of Colorado.

Marx, K. (1845). The German ideology. https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1845/german-ideology/ch01a.htm

Miller, P. H. (2011). Theories of Developmental Psychology (5th ed.). Worth Publishers. https://davcollegekanpur.ac.in/assets/ebooks/Psychology/Theories%20of%20Developemental%20Psychology%20by%20Miller.pdf

Moje, E. B., Collazo, T., Carrillo, R., & Marx, R. W. (2001). “Maestro, what is ‘quality’?”: Language, literacy, and discourse in project‐based science. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 38(4), 469–498. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.1014

Piaget, J. (1959). The language and thought of the child (3rd ed.) (M. Gabain & R. Gabain, Trans.). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Rogoff, B., Mistry, J., Göncü, A., Mosier, C., Chavajay, P., Heath, S. B., & Goncu, A. (1993). Guided participation in cultural activity by toddlers and caregivers. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 58(8), i. https://doi.org/10.2307/1166109

Soja, E. W. (1998). Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles and other Real-and-Imagined Places. Capital & Class, 22(1), 137–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/030981689806400112

Sole, M. (2016). Crib song: Insights into functions of toddlers’ private spontaneous singing. Psychology of Music, 45(2), 172–192. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735616650746

Tudge, J. R. H., & Winterhoff, P. A. (1993). Vygotsky, Piaget, and Bandura: Perspectives on the relations between the social world and cognitive development. Human Development, 36, 61.

Vygotsky, L. (1962). Thought and language. http://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA07207011

Vygotsky, L. (1978). Mind in Society: the development of higher psychological processes. https://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA03570814

Watson, S. L., & Reigeluth, C. M. (2016). The Learner-Centered paradigm of education. Routledge eBooks (pp. 21–48). https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315795478-10

Further Readings

Antil, L. R., Jenkins, J. R., Wayne, S. K., & Vadasy, P. F. (1998). Cooperative Learning: Prevalence, Conceptualizations, and the Relation between Research and Practice. American Educational Research Journal, 35(3), 419. https://doi.org/10.2307/1163443

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. General Learning Press.

Brame, C. (2013). Flipping the classroom. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. http://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/flipping-the-classroom/.

Bransford, J. D., Sherwood, R. D., Hasselbring, T. S., Kinzer, C. K., & Williams, S. M. (1990). Anchored instruction: Why we need it and how technology can help. In D. Nix & R. Sprio (Eds.), Cognition, education and multimedia (pp. 115-141). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum Associates.

Capraro, R. M., Capraro, M. M., Morgan, J. R. (2013). STEM project-based learning: An integrated science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) approach. Sense Publishers.

Donald J. Cunningham, Bonk, C. J., & Cunningham, D. J. (1998). Searching for Learner-Centered, constructivist, and sociocultural components of collaborative educational learning tools. Electronic collaborators: Learner-centered technologies for literacy, apprenticeship, and discourse (pp. 25–50). Indiana University. https://www.publicationshare.com/docs/Bon02.pdf

Faukner, D., Littleton, K., & Woodhead, M. (Eds.). (2013). Learning relationships in the classroom. Routledge.

Fogleman, J., McNeill, K. L., & Krajcik, J. (2011). Examining the effect of teachers’ adaptations of a middle school science inquiry-oriented curriculum unit on student learning. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 48(2), 149-169.

Garcia, E. (2017). A starter’s guide to PBL fieldwork. https://www.edutopia.org/article/starters-guide-pbl-fieldwork.

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2000). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2-3), 87-105.

Hickey, D. T., Moore, A. L., & Pellegrino, J. (2001). The motivation and academic consequences of elementary mathematics environments: Do constructivist innovations and reforms make a difference? American Educational Research Journal, 38(3), 611-652.

James, W., (1950, originally published 1890). The principles of psychology. Dover.

Kagan, S. (1999). The “E” of PIES. https://www.kaganonline.com/free_articles/dr_spencer_kagan/ASK05.php.

Kagan, S. (1994). Cooperative Learning. Kagan Publishing.

Kozulin, A. (1990). Vygotsky’s psychology: A biography of ideas. Harvard University Press.

Lally, M., & Valentine-French, S. (2019). Lifespan development: A psychological perspective (2nd ed.). OpenStax.

Lefrancois, G. R. (1999). Psychology for teaching (10th ed.). Wadsworth Thomson Learning.

Lou, N. & Peek, K. (2016, February 23). By the numbers: The rise of the makerspace. Popular Science, March/April 2016. http://www.popsci.com/rise-makerspace-by-numbers

Matusov, E. (2015). Comprehension: A dialogic authorial approach. Culture & Psychology, 21(3), 392-416.

Matusov, E. (2015). Vygotsky’s Theory of Human Development and New Approaches to education. Elsevier eBooks (pp. 316–321). https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-08-097086-8.92016-6

Miller, R. (2011). Vygotsky in perspective. Cambridge university press.

Oliver, K. M. (2016). Professional development considerations for makerspace leaders, part one: Addressing “what?” and “why?” TechTrends, 60 (2). pp. 160–166.

Palinscar, A. S. (1998). Keeping the metaphor of scaffolding fresh: A response to C. Addison Stone’s The metaphor of scaffolding: Its utility for the field of learning disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 31, 370-373.

Palincsar, A. S. (1998). Social constructivist perspectives on teaching and learning. Annual Review of Psychology, 49. pp. 345-375.

Resta, P. & Laferriere, T. (2007). Technology in support of collaborative learning. Educational Psychology Review, 19(1), 65-83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-007-9042-7

Scardamalia, M. & Bereiter, C. (1994). Computer support for knowledge building communities. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 3(3), 265-283.

Stahl, G., Koschmann, T., & Suthers, D. (2006). Computer-supported collaborative learning: An historical perspective. R. K. Sawyer (Ed.), Cambridge handbook of the learning sciences (pp. 409-426). Cambridge University Press.

Tomasello, M., Kruger A. C., & Ratner, H. H. (1993). Cultural learning. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 16(1), 495-552.

Wood, D. (1998). How children think and learn (2nd ed.). Blackwell.

Licenses and Attribution

Vygotsky’s Sociocultural Theory by Autumn Salsberry is adapted from the following sources:

- “Socioculturalism” by B. Allman from Educational Research Across Multiple Paradigms used under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License,

- “Language, Though, and Education: The Impact of Lev Vygotsky” by A. Pacheco from Observatory of the Institute for the Future of Education used under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License,

- “Vygotsky’s Sociocultural Theory of Cognitive Development” by T. LaMarr in Infant and Toddler Care and Development from The LibreTexts used under a Mixed 4.0 License,

- “Sociocultural Theory” by S. May-Varas, J. Margolis, and T. Mead in Educational Learning Theories from from Pressbooks used under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License,

- “Drew Polly, Bohdana Allman, Amanda Casto, Jessica Norwood” by R. West in Foundations of Learning and Instructional Design Technology from Pressbooks used under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, and

- “Vygotsky’s Sociocultural Theory” by M. Palm in Lifespan Human Development: A Topical Approach from Pressbooks used under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

In honor of the license requirements from the sources used throughout, Vygotsky’s Sociocultural Theory by Autumn Salsberry is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

AI Attribution: This work was primarily human-created. AI was used to make content edits, such as changes to scope, information, and ideas. AI was prompted for its contributions, or AI assistance was enabled. AI-generated content was reviewed and approved. The following model or application was used: Canva.