Self-Determination Theory

Shayla Nelson

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to…

- Describe the three basic psychological needs—autonomy, competence, and relatedness—that are part of Self-Determination Theory (SDT).

- Distinguish between motivation that comes from within (intrinsic) and motivation that comes from outside rewards (extrinsic).

- Explain how the main ideas of Self-Determination Theory can be used to design better learning experiences.

Introduction to Self-Determination Theory

Overview

Self-Determination Theory (SDT), developed by psychologists Edward Deci and Richard Ryan in the 1980s, is a theory about motivation. It focuses on intrinsic motivation, which is the kind of motivation that comes from inside a person, like curiosity or enjoyment. Unlike older theories that rely on outside rewards or punishments, SDT says that people are most motivated when three basic psychological needs are met: autonomy (having control), competence (feeling capable), and relatedness (feeling connected to others).

Deci and Ryan’s research showed that when learners get to make meaningful choices, build their skills, and form positive relationships, they become more motivated and engaged. Their work challenged earlier ideas that motivation only comes from outside rewards, like prizes or grades. Instead, they focused on what makes people feel personally satisfied and driven to learn on their own.

Understanding SDT can help instructional designers create learning environments—whether in classrooms, online courses, or workplace training—that build stronger motivation and long-term engagement by supporting these key needs.

Importance

SDT gives instructional designers a helpful way to understand how motivation affects learning. Instead of focusing on outside rewards or punishments, SDT looks at the internal needs that drive motivation from within. This helps explain why students are more likely to stay engaged, keep trying when things get hard, and take responsibility for their learning. When instructional designers understand this, they can create learning environments that support stronger, more lasting motivation.

Learning environments that support autonomy, competence, and relatedness help students succeed. When students have meaningful choices, chances to build their confidence, and positive connections with teachers and classmates, they are more likely to enjoy learning and stay involved. For instructional designers, SDT offers a way to build student-centered learning that feels meaningful and motivating.

SDT is also useful outside of school. It can help in workplace training, career development, and programs that encourage behavior change. In all of these areas, people tend to stay motivated when their basic psychological needs are supported (Deci & Ryan, 2008).

Origins of Self-Determination Theory

Founders

SDT was created by two psychologists, Edward Deci and Richard Ryan, in the 1980s. They wanted to better understand what motivates people to learn and grow. Their work built on older ideas, such as Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Maslow believed that people must meet their basic needs, like food and safety, before they can focus on learning or personal growth.

Deci and Ryan had a different view. They said that three needs—autonomy (having control), competence (feeling capable), and relatedness (feeling connected to others)—are always important. These needs influence motivation no matter what else is going on in someone’s life.

Deci’s early research showed that outside rewards, like money or prizes, can sometimes lower motivation. On the other hand, curiosity and enjoyment can increase it. This went against the popular idea at the time that rewards always help people try harder. Later, Ryan joined Deci, and they worked together to explain how motivation can move along a scale. On one end, motivation is controlled by others. On the other end, it is completely self-driven. The closer motivation is to the self-driven side, the stronger it tends to be.

Over time, their research helped people see motivation differently. They showed that when schools, workplaces, or other environments support these three basic needs, people are more motivated and engaged. Their work continues to influence how we design learning today.

Historical Context

SDT was created as a response to behaviorism, a popular theory during the mid-1900s. Behaviorism explained motivation by focusing on rewards and punishments. It looked mostly at how to control behavior through things like praise, prizes, or consequences. This approach often ignored students’ personal choices, goals, and interests.

In the 1970s, researchers began to question this way of thinking. Edward Deci’s research showed something surprising. When people were given rewards for things they already enjoyed doing, they sometimes became less interested. This is called the overjustification effect (Deci, 1971). Later research showed that rewards can not only lower motivation but also make people depend on those rewards to keep trying (Deci et al., 1999).

Others also criticized behaviorism. DeGrandpre (2000) said that behaviorism misses the reasons behind people’s actions and ignores their background or culture. Kohn (1996) warned that using too many rewards or punishments in the classroom can make students feel less in control and less motivated over time. These ideas supported what SDT believes—that students are more motivated when they have a sense of choice, purpose, and connection.

By the late 1900s, Deci and Ryan had fully developed SDT. They showed that motivation comes from meeting important psychological needs, not just from getting rewards or avoiding punishment. Their work helped shift motivation research in a new direction. It led to more focus on giving students freedom to make choices, opportunities to grow their skills, and support to feel connected to others. Today, SDT continues to shape how teachers, trainers, and instructional designers think about motivation.

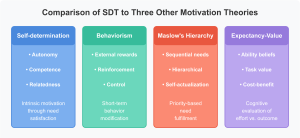

Comparison with Other Theories

SDT is different from other motivation theories because it focuses on what people need to feel motivated from within. While some theories talk more about rewards or fixed steps of growth, SDT highlights how important it is for people to feel in control, capable, and connected.

SDT vs. Behaviorism

Behaviorism says that people are motivated by rewards and punishments. SDT disagrees. It shows that rewards can sometimes make people less interested, especially if those rewards take away their sense of choice (Deci et al., 1999). Behaviorism might work in the short term, but SDT focuses on building motivation that lasts.

SDT vs. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Maslow’s theory says that people must meet their basic needs, like food and safety, before they can grow and learn. SDT offers a different idea. It says that autonomy, competence, and relatedness are always important and always influence motivation. People don’t have to wait to meet other needs first.

SDT vs. Expectancy-Value Theory

Expectancy-Value Theory explains motivation based on two things: whether a person believes they can succeed and how much they value the task (Eccles & Wigfield, 2002). SDT agrees that confidence is important but adds that people also need choice and connection. Even if students feel confident and see value in a task, they may not stay motivated if they don’t feel connected or in control.

Each of these theories helps us understand motivation in different ways. But SDT is especially helpful for showing how to create learning environments that support motivation over time.

This figure compares SDT with three other major motivation theories. Each one has a different way of explaining what drives people to act:

Fundamental Tenets of Self-Determination Theory

Key Concepts

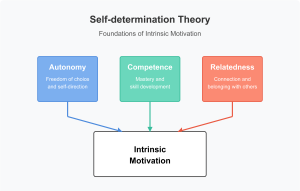

SDT explains that human motivation is shaped by three core psychological needs: autonomy, competence, and relatedness. When these needs are met, people are more likely to feel motivated from within, leading to stronger focus, more effort, and greater well-being. But when these needs are not met, motivation tends to come from outside pressure, which can lower interest and reduce independent learning.

Here’s what each need means and how it supports motivation:

Autonomy

Autonomy is the need to feel in control of your own actions. People are more motivated when they can make choices and feel like their actions matter. In school, this might look like letting students choose their project topics or how they want to show their learning. Having choices helps students feel more invested and interested in what they’re doing.

Competence

Competence is about feeling capable and successful. It grows when students get helpful feedback, face just the right amount of challenge, and see progress in their skills. For example, if a teacher gives a student clear feedback on their writing, the student can improve and feel more confident. That confidence encourages them to keep trying and take on more complex tasks.

Relatedness

Relatedness is the need to feel connected to other people. Students are more motivated when they feel supported and valued by their teachers and classmates. Things like group discussions or partner activities help build this connection. When students feel like they belong, they’re more likely to stay engaged and participate.

Unlike some other theories that describe needs in a fixed order, SDT sees autonomy, competence, and relatedness as equally important. They work together all the time—not one after the other. When all three are supported, students are more likely to stay motivated because they find meaning in what they’re doing.

Test your understanding of the key concepts of SDT with the following H5P activity.

Supporting Mechanisms

SDT explains that there are two main types of motivation: intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivation.

- Intrinsic motivation happens when people do something because they enjoy it or find it interesting. This type of motivation often leads to better learning, more creativity, and stronger effort.

- Extrinsic motivation happens when people do something for a reward or to meet an outside expectation. This could include money, grades, praise, or pressure from others.

SDT looks at extrinsic motivation more closely. It shows that there are different levels of it, depending on how much people accept the reasons behind their actions. These levels are explained on a scale called the motivation continuum:

- External Regulation – A person acts only to get a reward or avoid a punishment. For example, a student studies just to avoid failing a test.

- Introjected Regulation – A person acts because of guilt or pressure, even if it does not feel like a true choice. For example, they do an assignment because they would feel bad if they did not.

- Identified Regulation – A person sees value in the task, even if they did not choose it at first. For example, they learn math because they know it will help with their future career.

- Integrated Regulation – A person’s actions match their personal values and goals. Even if the task came from outside, it now feels like a part of who they are. For example, they study because learning is something they care about deeply.

Over time, people can move from external to more internal motivation. This process is called internalization. It happens when someone begins to take in outside goals and make them their own. Deci’s research found that certain things help with this shift, such as offering choices, giving helpful feedback, and encouraging positive social interactions.

By understanding the different types of motivation and how people internalize outside influences, SDT gives us a useful way to think about motivation in many settings. These ideas can help us design learning environments that keep students engaged, help them manage their own learning, and stay motivated for the long term.

Use the H5P activity below to decide whether each example shows intrinsic or extrinsic motivation.

Strengths and Limitations of Self-Determination Theory

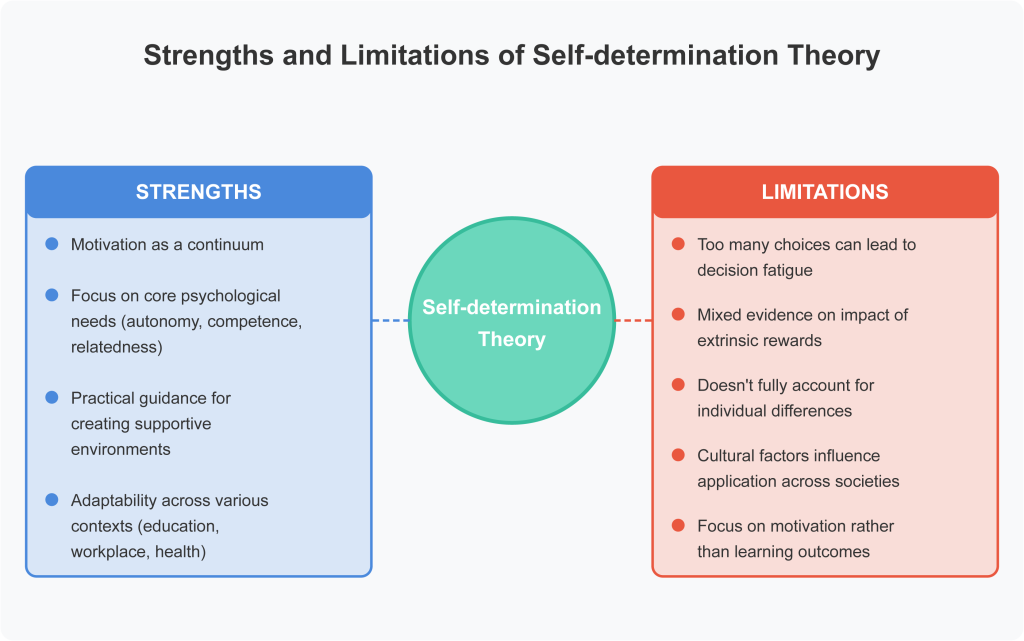

Now that we’ve looked at the different types of motivation in SDT, it’s helpful to take a step back and think about what the theory does well and where it has limits. Like any theory, SDT is not perfect, but it offers many useful ideas for learning and teaching.

Strengths

SDT gives us a better way to understand why people care about what they are doing. One of its biggest strengths is that it shows motivation on a scale. Instead of saying motivation is only either “intrinsic” or “extrinsic,” SDT explains that there are different levels in between. This makes it easier to apply in real-life situations.

SDT also shows how to increase motivation in healthy ways. People are more motivated when they have choices, get helpful feedback, and feel connected to others. For example, students who get to choose their project topic or work in a group often feel more excited to participate. In the workplace, employees who can set their own goals and get support from others are usually more satisfied and willing to improve.

Another strength of SDT is that it gives a clear focus on three important needs: autonomy, competence, and relatedness. When people feel in control, feel capable, and feel connected, they are more likely to stay motivated. This gives teachers and instructional designers a solid foundation for creating lessons that support student success. Classrooms that support these needs—for example, by offering choice, giving helpful feedback, and encouraging group work—often lead to better learning and stronger motivation (Ryan & Deci, 2000).

Finally, SDT can be used in many different places, including schools, training programs, sports, and healthcare. Because it is based on basic human needs, it works across many situations and cultures (Deci & Ryan, 2008).

Limitations

Even though SDT has many strengths, it also has some challenges. One issue is that giving people too much choice can sometimes backfire. If students are given too many options without support, they might feel confused or stressed (Schwartz, 2004). For example, in an online class, too many assignment choices could make students unsure of what to do, which can lower motivation.

Another challenge is that not all rewards reduce motivation. While SDT says rewards can be harmful, some studies show that certain rewards—like surprise praise or kind words—can actually help. In schools and workplaces, small rewards can sometimes encourage people to stay on task without hurting their internal motivation (Cameron & Pierce, 1994).

SDT also does not explain why some people need more support than others. Some students do well with a lot of freedom, while others need clear steps and strong guidance. For example, students with attention challenges may find it hard to stay motivated in a learning environment that is too flexible. Cultural differences matter too. In some cultures, learning works better when teachers lead the process and group goals are more important than personal ones (Chirkov et al., 2003).

Finally, SDT focuses a lot on motivation but less on direct learning outcomes. Motivation can help with success, but things like teaching quality, background knowledge, and learning strategies also matter (Schwartz, 2004). This means that SDT is helpful, but it works best when used alongside other ideas that focus more on how students learn.

This figure shows a balanced view of SDT. It highlights what the theory does well and where more research or support may be needed:

Instructional Design Implications

Practical Applications

SDT offers practical ideas that can help teachers and instructional designers create learning environments where students are more likely to stay motivated. When students feel supported in the areas of autonomy, competence, and relatedness, they are more likely to enjoy learning and stay engaged.

Supporting Autonomy

- Give students meaningful choices in what and how they learn, such as picking their project topics or choosing how to show what they’ve learned (Ryan & Lynch, 2003).

- Encourage students to take control of their learning by setting their own goals and tracking their progress.

- Use teaching methods that allow for student voice and creativity, like project-based learning, inquiry-based lessons, or student-led discussions.

Fostering Competence

- Design tasks that are interesting but still manageable. Make sure students have the support they need to succeed.

- Give clear and helpful feedback so students can build their skills and know how they’re doing (Elliott et al., 2004).

- Use grading and assessments that focus on growth and improvement, not just scores or competition.

Enhancing Relatedness

- Create opportunities for students to work together through group projects, discussions, or problem-solving activities.

- Build positive teacher-student relationships by noticing students’ efforts, giving encouragement, and communicating often (Ryan & Lynch, 2003).

- Make the learning environment welcoming and respectful so all students feel like they belong.

This figure shows a key idea from SDT: when autonomy, competence, and relatedness are supported, students are more likely to feel motivated and do well in school:

Example Application

In a history class, SDT principles can be used in the following ways:

- Autonomy: Students can choose how they want to show their learning. They might write an essay, create a slideshow, or organize a class debate.

- Competence: Teachers can give feedback on early drafts to help students improve before turning in their final work. This helps students build their skills and feel more confident.

- Relatedness: Group work, such as analyzing primary sources with classmates, gives students a chance to share ideas and build connections with others.

By using these ideas, teachers can move beyond simply getting students to complete assignments. Instead, they can create learning experiences that help students stay engaged, build confidence, and keep learning.

Strategies

To use SDT effectively, educators should design lessons that support students’ psychological needs. At the same time, they should reduce the use of rewards or punishments as the main reason for learning.

Strategies to Support Autonomy

- Explain why learning activities matter so students see the purpose.

- Give students choices about how they learn and show their understanding.

- Use helpful, encouraging language instead of commands or pressure.

Strategies to Build Competence

- Use scaffolding. This means giving support at first, then slowly stepping back as students build confidence.

- Give clear and specific feedback that helps students improve (Elliott et al., 2004).

- Use assessments that focus on progress and growth, not just scores or competition.

Strategies to Foster Relatedness

- Encourage group work, peer discussions, and team activities.

- Build a classroom community where students feel valued and supported.

- Show students that their ideas matter by recognizing their efforts and communicating with care.

These strategies help students feel more motivated and confident. They also support students in becoming more independent in how they learn and manage their work.

Reflection Prompt

When you plan a lesson or activity, which of the three SDT needs – autonomy, competence, or relatedness – do you usually focus on the most? Which one do you think you could include more in your future work?

Contexts

The basic needs in SDT—autonomy, competence, and relatedness—are important for all learners. But the way we support those needs can look different depending on the learning environment. The examples below show how these ideas can be used in both traditional classrooms and online learning.

Traditional Classrooms

- Let students choose some of their assignments, such as picking their own research topic. This helps support autonomy.

- Use small group discussions, debates, or team projects to build relatedness and help students feel connected.

- Focus on growth by using grading methods that reward effort and improvement, not just final scores (Niemiec & Ryan, 2009).

Online Learning

- Design lessons that allow students to move at their own pace and explore content in different ways. This helps support autonomy.

- Give students fast, clear feedback through quizzes or comments, so they can track their progress and feel more confident.

- Create places for students to connect, such as discussion forums, breakout rooms, or shared projects, to support relatedness.

The following case study shows how an instructional designer used SDT in a real course to help students feel more confident and connected.

Case Study: Enhancing Competence and Relatedness in a STEM Course

Context:

David is an instructional designer at a community college. He is working on a beginning programming course for STEM students. In the past, many students struggled with the hard content and felt isolated because the course was self-paced.

Challenge:

To help students feel more motivated, David uses Self-Determination Theory. He focuses on two needs: competence and relatedness. First, he redesigns the course to include coding assignments that increase in difficulty over time. These assignments come with instant feedback to help students build their skills and feel more confident. Then, he adds group coding labs and a peer-mentorship program so students can connect with others and feel supported.

Outcome:

The new course received positive feedback. Students said they felt more confident and more connected to others. Fewer students dropped the course, and average scores went up. David believes that supporting the needs for competence and relatedness made a big difference in how motivated students felt.

Application:

This case study shows how SDT can be used in instructional design. By helping students build skills and feel connected, teachers and designers can improve motivation, effort, and success. Feedback and peer interaction are powerful ways to support student learning in many different types of classes.

Corporate Training & Professional Development

The ideas in SDT are not just for schools. They also work well in job training, professional development, and other learning programs for adults. People in the workplace are more motivated when their learning supports their personal goals and interests.

Here are some ways SDT can be used in corporate training:

- Connect training to employees’ career goals or interests. This supports autonomy and competence.

- Let employees set their own learning goals and choose the best way to meet them. This gives them more control and helps with motivation.

- Build a positive work culture that encourages teamwork, independence, and growth. When people feel supported and included, they are more likely to stay motivated.

No matter the setting, motivation improves when people feel in control, believe in their abilities, and feel connected to others. By using SDT in different learning environments, educators, trainers, and designers can help learners stay motivated and succeed.

Conclusion

SDT helps us understand what keeps people motivated, especially in learning environments. Instead of focusing on rewards or punishments, SDT shows that people learn best when they feel in control, feel capable, and feel connected to others.

This theory can be used in many places, such as classrooms, online courses, and workplace training. As new tools like adaptive learning and real-time feedback become more common, SDT gives teachers and designers a strong way to create learning that feels personal and meaningful.

For instructional designers, this means thinking about how to support choice, growth, and connection in every lesson. When we focus on these three needs, we can help learners stay motivated, keep trying, and enjoy learning—not just for school, but for life.

Use the H5P below to review what you have learned about how SDT can be used in instructional design.

Reflection Prompt

Think about a course you have taken or helped design. Were any of the SDT needs—autonomy, competence, or relatedness—supported well? Was there one that was missing? How did that affect your motivation or the motivation of others?

References

Cameron, J., & Pierce, W. D. (1994). Reinforcement, reward, and intrinsic motivation: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 64(3). https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543064003363

Chirkov, V., Ryan, R. M., Kim, Y., & Kaplan, U. (2003). Differentiating autonomy from individualism and independence: A self-determination theory perspective on internalization of cultural orientations and well-being. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 34(6). https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022103250691

Deci, E. L. (1971). Effects of externally mediated rewards on intrinsic motivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 18(1). https://doi.org/10.1037/h0030644

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Plenum Press.

Deci, E. L., Koestner, R., & Ryan, R. M. (1999). A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 125(6). https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.125.6.627

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4). https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2008). Self-determination theory: A macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Canadian Psychology, 49(3). https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012801

DeGrandpre, R. J. (2000). A science of meaning: Can behaviorism bring meaning to psychological science? American Psychologist, 55(7). https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.7.721

Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2002). Motivational beliefs, values, and goals. Annual Review of Psychology, 53(1). https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135153

Elliott, A. J., McGregor, H. A., & Thrash, T. M. (2004). The need for competence. In E. L. Deci & R. M. Ryan (Eds.), Handbook of self-determination research. University of Rochester Press.

Kohn, A. (1996). Beyond discipline: From compliance to community. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Niemiec, C. P., & Ryan, R. M. (2009). Autonomy, competence, and relatedness in the classroom: Applying self-determination theory to educational practice. Theory and Research in Education, 7(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/1477878509104318

Ryan, R. M., & Lynch, M. F. (2003). Philosophies of motivation and classroom management. In R. Curren (Ed.), Blackwell companion to philosophy: A companion to the philosophy of education. Blackwell.

Schwartz, B. (2004). The paradox of choice: Why more is less. Ecco.

Licenses and Attribution

“Self-Determination Theory” by Shayla Nelson is adapted from:

- “Motivation Theories and Instructional Design” by S. Park, in R. West, Foundations of Learning and Instructional Design Technology from EdTech Books, used under a CC BY 4.0 license

- “Motivation Theories on Learning” by K. Seifert & R. Sutton, in R. West, Foundations of Learning and Instructional Design Technology from EdTech Books, used under a CC BY 4.0 license

- “Motivation” by G. Mullin, in Introduction to Psychology from Achieving the Dream, used under a CC BY 4.0 license

- “Learning Theories” by S. Conklin & B. Oyarzun, in McDonald, J.K. & R. West, Instructional Design from EdTech Books, used under a CC BY-NC 4.0 license

“Self-Determination Theory” by Shayla Nelson is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

AI Attribution: AIA HAb SeNc Hin R ChatGPT, Claude v1.0