Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Dave Smith

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Identify the levels of the hierarchy of needs

- Identify the fundamental assumptions of the hierarchy of needs

- Identify the fundamental differences between humanistic, behaviorism and psychoanalytical psychology.

- Identify educational design processes associated with the hierarchy of needs

Introduction

Overview

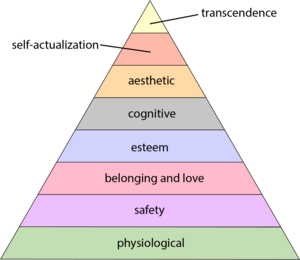

At the base of the pyramid are all of the physiological needs that are necessary for survival. These are followed by basic needs for security and safety, the need to be loved and to have a sense of belonging, and the need to have self-worth and confidence. The top tier of the pyramid is self-actualization and transcendence, which is a need that essentially equates to achieving one’s full potential, and it can only be realized when needs lower on the pyramid have been met. To Maslow and humanistic theorists, self-actualization reflects the humanistic emphasis on positive aspects of human nature, (Francis & Kritsonis, 2006; Maslow, 1943).

Origins of the Learning Theory

Founder

Historical Context

- to understand ourselves and others holistically (as being greater than the sums of their parts)

- to acknowledge the relevance and significance of the history of an individual

- to acknowledge the importance of human existence

- to recognize the importance of an end goal of life for a healthy person

Comparison with Other Theories

- Freud’s psychoanalytical theory was deterministic, meaning that peoples unconscious desires controlled their behaviors and that their behavior was outside of their control (Khan Academy, 2013).

- Skinner’s behaviorism was too focused on outside rewards and consequences to drive motivation and did not rely enough on intrinsic feedback mechanisms.

- Freud and Skinner’s theories focused only on individuals with mental conflicts (pathological) rather than all individuals (well and unwell).

- The other two theories focused too much on the negative traits of human beings, rather than focusing on the positive power Maslow believed individuals to have.

Fundamental Tenets of the Theory

Human needs as identified by Maslow:

(Click the information bubbles in the image below to learn more about each level)

The bottom four levels are known as Deficiency needs or D-needs. This means that if there are not enough of one of those four needs, there will be a need to get it. Getting them brings a feeling of contentment. These needs alone are not motivating but rather seen as fundamental for living (Boeree, 2006). The top four levels are known as Building needs or B-needs. These needs move an individual away from basic survival and towards reaching their full potential. Achievement of one of these levels requires a higher level of motivation and can be viewed as becoming self fulfilled.

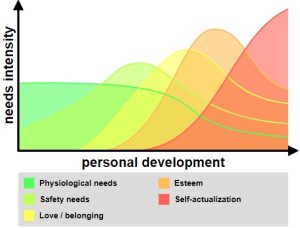

In contrast to the well-known pyramid, a number of alternative illustrations of the Hierarchy of Needs have been developed. One of the earliest shows a more dynamic hierarchy represented as ‘waves’ of different needs overlapping at the same time (Krech et al., 1962). As illustrated, the peak of an earlier set of needs must be passed before the next ‘higher’ need can begin to assume a dominant role. Achieving fulfillment of a need does not mean that need goes away, it simply means that we are now able to prioritize higher level needs above the lower level needs.

Match the hierarchy level names with their appropriate position on the pyramid.

Strengths and Limitations of the Theory

Strengths

Limitations

Instructional Design Implications

Practical Applications

Addressing Basic Needs (Physiological & Safety)

- Lesson Design: Ensure students have access to learning materials in formats that accommodate different needs.

- Assessments: Minimize test anxiety by providing clear instructions, practice opportunities, supportive feedback, flexible deadlines and/or alternative assessments.

- Lesson Design: Foster collaborative learning through group discussions, peer feedback, and cooperative projects to build a sense of community.

- Assessments: Use formative assessments that encourage dialogue, such as peer reviews or group presentations.

- Lesson Design: Design tasks with scaffolded difficulty levels to allow students to experience small wins before tackling more challenging concepts.

- Assessments: Provide constructive feedback that highlights strengths and areas for improvement rather than just pointing out mistakes.

Fostering Intellectual Curiosity (Cognitive)

- Lesson Design: Design learning experiences that challenge students to ask questions, explore different perspectives, and make connections between ideas.

- Assessments: Use assessments that go beyond rote memorization, such as problem-solving tasks, debates, or concept mapping.

Inspiring an Appreciation for Beauty and Structure (Aesthetic)

- Lesson Design: Incorporate elements of music, art, storytelling, or real-world design to enrich content delivery.

- Assessments: Allow students to express their understanding in creative formats, such as multimedia projects, artistic representations, or well-structured presentations.

Encouraging Personal Growth (Self-Actualization)

- Lesson Design: Allow students to pursue topics of personal interest within the curriculum.

- Assessments: Incorporate authentic assessments like case studies, simulations, or open-ended projects.

Cultivating a Higher Purpose in Learning (Transcendence)

- Lesson Design: Encourage students to connect their learning to a broader purpose, such as contributing to society, solving global challenges, or mentoring others.

- Assessments: Incorporate projects that emphasize real-world impact, such as community outreach initiatives, advocacy campaigns, or mentorship programs.

Case Study – Applying Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs to an educational setting

(Written with the help of Chat GPT)

Background

Lincoln High School struggled with student engagement and academic performance. Many students came from low-income backgrounds, faced food insecurity, and lacked stable home environments. Teachers observed that traditional instructional strategies were not yielding the expected outcomes, prompting the administration to explore new approaches rooted in educational psychology.

Intervention

The school adopted a framework based on Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, ensuring that students’ basic needs were met before expecting high levels of academic achievement. The intervention included:

-

- Physiological Needs: The school introduced a breakfast and lunch program that provided free, nutritious meals to all students.

- Safety Needs: Security measures were enhanced, including anti-bullying programs, counseling services, and a mentorship initiative that connected students with trusted adults.

- Belongingness and Love Needs: Teachers fostered a more inclusive and supportive classroom culture by implementing cooperative learning strategies, peer mentoring, and student clubs.

- Esteem Needs: Recognizing student achievements beyond academics, such as personal growth and leadership, helped build confidence.

- Cognitive Needs: Inquiry-based learning and project-based assignments encouraged curiosity and independent thinking.

- Aesthetic Needs: The school expanded its arts and music programs, offering theater, dance, visual arts, and digital media courses.

- Self-Actualization: Students were engaged in creative and higher-order thinking activities. Project-based learning and student-led initiatives empowered them to explore their interests and develop problem-solving skills.

- Transcendence: The school created a Global Citizenship Initiative, where students explored humanitarian efforts, sustainability projects, and social justice movements.

Outcome

Over two academic years, Lincoln High School saw a 20% increase in student attendance, a 15% improvement in standardized test scores, and a notable decline in behavioral incidents. Surveys indicated that students felt more supported and motivated to learn. Teachers reported higher levels of classroom engagement and fewer disruptions, reinforcing the idea that addressing fundamental human needs enhances learning outcomes.

In this practical application, align the paragraphs describing a level of the hierarchy of needs with its appropriate level on the pyramid. Note: the boxes on the left are not shown in order of hierarchy.

Conclusion

References:

Berger, K. S. (1983). The developing person through the life span. Worth Publishers.

Boeree, C. (2006). Abraham Maslow. Webspace.ship.edu. Archived from the original on April 30, 2016. Retrieved October 21, 2012.

Carlson, N.R., Miller, H.L., Heth, D.S., Donahoe, J.W., & Martin, G.N. (2007). Psychology: The science of behaviour. (4th ed.). Pearson Education Canada.

Francis, N. H., & Kritsonis, W. A. (2006). A brief analysis of Abraham Maslow’s original writing of Self-Actualizing people: A study of psychological health. Doctoral Forum National Journal of Publishing and Mentoring Doctoral Student Research, 3, 1–7.

Frick, W. B. (1989). Interview with Dr. Abraham Maslow. In Humanistic Psychology: Conversations with Abraham Maslow, Gardner Murphy, Carl Rogers (pp. 19–50). Wyndham Hall Press.

Hoffman, E. (1988). The right to be human: A biography of Abraham Maslow. St. Martin’s Press.

Khan Academy. (2013, September 13). Humanistic theory | Behavior | MCAT | Khan Academy [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3UcjojHetfE

Krech, D., Crutchfield, R. S., & Ballachey, E. L. (1962). Individual in society: A textbook of social psychology. McGraw Hill.

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50, 370–396.

Maslow, A. H. (1967). A theory of metamotivation: The biological rooting of the Value-Life. Journal of Humanistic Psychology. 7 (2): 93–126. doi:10.1177/002216786700700201.

The New York Times. (1970, June 10). Dr. Abraham Maslow, Founder Of Humanistic Psychology, Dies. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1970/06/10/archives/dr-abraham-maslow-founder-of-humanistic-psychology-dies.html

Image Descriptions

Figure 1. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs visualized as a pyramid. The image depicts a pyramid divided into eight colored sections, each representing a different level of human needs. From bottom to top: the largest green section labeled “physiological”; a purple section labeled “safety”; a pink section labeled “belonging and love”; a blue section labeled “esteem”; a gray section labeled “cognitive”; an orange section labeled “aesthetic”; red section labeled “self-actualization”; and a yellow section labeled “transcendence”. The pyramid illustrates a hierarchy, with basic needs at the bottom and more abstract needs towards the top. Each level slightly decreases in size towards the peak, creating an overall triangular shape. [Return to Figure 1]

Figure 3. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs visualized as waves. The image is a graph illustrating Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, represented by overlapping colored layers. The horizontal axis is labeled “personal development” and the vertical axis is labeled “needs intensity,” indicated by a double-headed arrow. Five colored layers denote different needs, each with varying widths along the development axis: green for “Physiological needs,” light green for “Safety needs,” yellow for “Love/belonging,” orange for “Esteem,” and red for “Self-actualization.” Each layer increases in height, peaks, and then tapers off as it progresses along the axis. A legend in the bottom right matches the colors to their corresponding needs categories. [Return to Figure 3]

Licenses and Attribution

“Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs” by Dave Smith is adapted from the following resources:

- “10.1 Motivation – Psychology” by Openstax used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license

- “Abraham Maslow” by Wikipedia used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license

- “Humanistic Psychology” by Wikipedia used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license

- “Maslow’s hierarchy of needs” by Wikipedia used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license

- “Own work” by Philipp Guttmann used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license

- “Maslow’s Hierarchy” by EucalyptusTreeHugger used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license

- “Needs-Based Theories of Motivation” by Lumen used under a CC BY 4.0 license

“Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs” by Dave Smith is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

AI Attribution: This work was primarily human-created. AI was used to make stylistic edits, such as changes to structure, wording, and clarity. AI was prompted for its contributions, or AI assistance was enabled. AI-generated content was reviewed and approved. The AI tool used was ChatGPT.