Leontiev’s Activity Theory

Lisa Costa

Learning Objectives

Type your learning objectives here.

- Identify Activity Theory theorists

- Identify key components of Activity Theory

- Identify fundamental assumptions of Activity Theory

Introduction to the Learning Theory

In this video, Lisa Costa introduces Activity Theory, a learning theory framework that emphasizes learning through purposeful, goal-directed activities within a social and cultural context. She explains how this theory helps instructional designers create engaging, real-world learning experiences and highlights key concepts like subjects, objects, tools, and communities. Costa also demonstrates how Activity Theory can be applied in educational settings to enhance collaboration and problem-solving.

Activity Theory (AT) is a learning framework that focuses on understanding human learning and development as a social and goal-directed process. It emphasizes that learning is not an isolated event but occurs through purposeful interaction within a community. The key theorists associated with AT include Lev Vygotsky, Alexei Leont’ev, and Sergei Rubinstein. Vygotsky’s cultural-historical psychology laid the foundation for AT by highlighting the role of social and cultural context in cognitive development. Leont’ev further developed the theory by focusing on the structure of human activity, which are goal-oriented, socially mediated, and shaped by tools and artifacts. Rubinstein contributed to the philosophical underpinnings of the theory, particularly regarding the neurophysiological and systemic aspects of human activity.

AT is significant in both education and psychology because it shifts the focus from individual cognitive processes to the social, cultural, and historical contexts that shape learning. This approach is especially important in understanding how knowledge is constructed not just by individuals but within a social context, where tools and social interactions play a pivotal role. In education, AT informs instructional design by emphasizing collaborative, context-rich learning environments that mirror real-world tasks, enabling students to develop skills through social interaction and the use of tools. It also addresses specific aspects of learning and development by framing them as part of a dynamic activity system, where contradictions and tensions within an organization can drive transformation and cognitive growth.

Origins of the Learning Theory

Activity Theory (AT) originated from the collaborative work of Alexei N. Leont’ev, Lev Vygotsky, and Alexander Luria at the Moscow State University in the early 20th century but mainly attributed to Leont’ev. Vygotsky’s cultural-historical psychology laid the foundation for AT, emphasizing that human development is shaped through social and cultural contexts, particularly through the use of artifacts. Leont’ev, building on Vygotsky’s principles, developed AT further by focusing on the structure of human activity systems and how they mediate between individuals and society. His work, refined at the Kharkov School of Psychology and Moscow State University, emphasized the dynamic interaction of individuals, tools, and societal structures in shaping human cognition.

In the late 1980s, Yrjö Engeström expanded on Leont’ev’s work by elaborating on the central concepts of cultural-historical activity theory and creating the structure of a human activity system. Influenced by neurophysiological research from Russian scientists like Anokhin and Bernstein, as well as philosophical contributions from Sergei Rubinstein, AT also developed into Systemic-Structural Activity Theory. Engeström’s work further shaped AT’s application in the Western world, particularly in the fields of expansive learning and organizational development. Together, these theorists and events have created the rich, interdisciplinary framework of Activity Theory.

Activity Theory (AT) differs from other learning theories like behaviorism, cognitivism, and constructivism by emphasizing the social, cultural, and systemic aspects of learning. Unlike behaviorism, which focuses on external stimuli and observable behavior, AT views learning as an active, goal-directed process shaped by the interaction between individuals, tools, and their community, where tools mediate cognitive development. In contrast to cognitivism, which concentrates on internal mental processes in isolation, AT highlights the importance of social context and collaboration, integrating the learner into an activity system that includes social structures and cultural artifacts. While constructivism shares AT’s view of active learning, AT extends this by focusing on the collective nature of learning, with an emphasis on how community roles and the division of labor shape knowledge creation. AT’s interdisciplinary nature, integrating psychology, sociology, and education, and its focus on tools as mediators of learning, set it apart from other theories, providing a broader, more comprehensive framework for understanding how learning occurs in real-world contexts.

Fundamental Tenets of the Theory

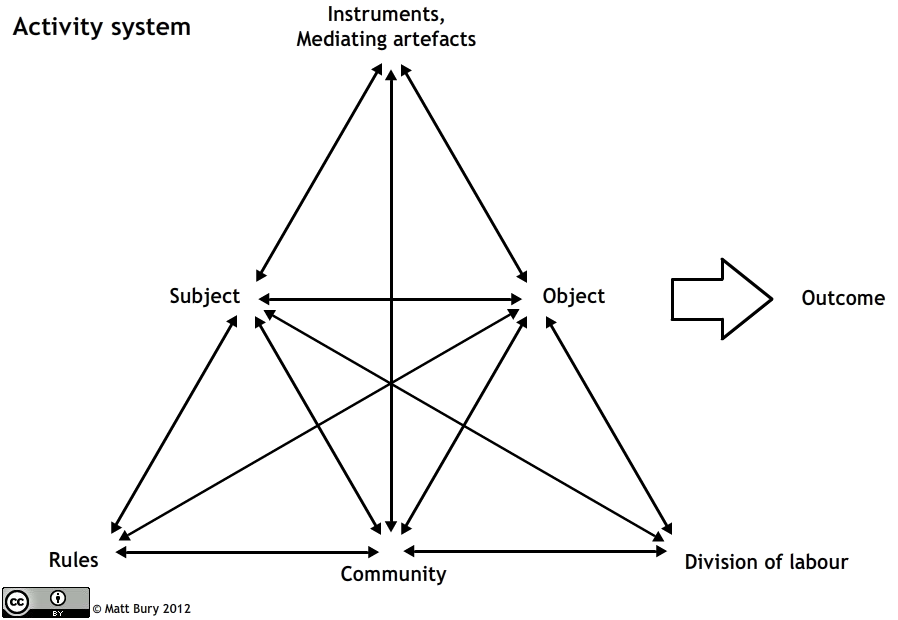

At its core, Activity Theory (AT) emphasizes that human activity is goal-directed, socially situated, and mediated by tools and artifacts. Learning and development occur within a collective system that includes the subject (learner), object (goal), tools (material and abstract), community (social context), rules, and division of labor (roles). It underscores that learning is not solely internal but shaped by interaction within a social context, with tools mediating actions and engaging individuals in shared activities. AT also highlights how contradictions and tensions within the activity system—such as between tools, actions, roles, and goals—can drive change and innovation. In real-world learning scenarios, this manifests in environments like classrooms and corporate training, where learners use tools to engage with others, solve problems, and construct knowledge, reflecting the social nature of learning and the impact of community and tools on cognitive and social development.

Image description: The image is a diagram titled “Activity system,” consisting of a triangular structure with various interconnected elements. At the top of the triangle is the label “Instruments, Mediating artefacts,” pointing downward with two arrows, one toward the “Subject” on the left and the other toward the “Object” on the right. The “Subject” and “Object” are positioned midway down the left and right sides of the triangle, respectively, connected by a horizontal arrow. At the base of the triangle, there is “Community” at the bottom center, “Rules” at the left corner, and “Division of labour” at the right corner. Arrows connect these elements to each other and to the “Subject” and “Object.” An arrow leads from the “Object” to a labeled “Outcome” on the right, outside the triangle. There is a copyright notice at the bottom left corner: “© Matt Bury 2012” along with Creative Commons symbols.

Case Study

Sarah is an instructional designer at Banks University. She has been tasked with creating an online course for graduate students in educational psychology. Sarah’s goal is to design a learning experience that reflects the collaborative, socially situated nature of learning as described in Leontiev’s Activity Theory (AT).

Sarah’s Goals:

- Ensure the course facilitates the development of both cognitive skills and social interaction, emphasizing the importance of tools, community, and goal-directed activity.

- The online course must focus on real-world application and collaboration, without the face-to-face interactions that typically occur in traditional classrooms.

- Develop learning activities and assessments that allow students to interact with each other and the course content in meaningful ways, using tools that mediate their learning.

AT Framework:

- Subject: Graduate students enrolled in the course.

- Object: Understanding and applying Activity Theory in educational contexts.

- Tools: Digital platforms (e.g., learning management system, collaboration tools such as Google Docs, discussion boards, and project management tools).

- Community: The cohort of students, the instructor, and guest experts or industry practitioners who can provide feedback on students’ ideas.

- Rules: Course guidelines, group project expectations, deadlines, and communication protocols.

- Division of Labor: Students are assigned roles within group projects, with specific tasks related to different aspects of Activity Theory (e.g., researching tools and artifacts, examining case studies, presenting findings).

Design Strategy:

Sarah designs a group-based project where students will collaborate to analyze a real-world classroom or educational setting through the lens of Activity Theory. Each group will examine how the system components (subject, object, tools, rules, community, division of labor) interact in a specific context, such as a school, a corporate training program, or a non-traditional learning environment. Students are assigned specific roles within their groups (e.g., researcher, coordinator, tool expert, presenter).

- Tools: Students will use collaborative platforms like Google Docs for real-time collaboration, video conferencing tools for group discussions, and shared digital whiteboards to visually map the activity system.

- Students are asked to document their experiences with the project, the tools they used, and how their understanding of Activity Theory evolved through collaboration.

- Community: Students will work closely with their peers in groups and will also interact with the instructor through regular check-ins and feedback sessions.

Assessment:

Students apply the principles of AT to redesign an educational activity they are familiar with, either from their own practice or from case studies presented in class.

Strengths and Limitations of the Theory

One key strength AT offers is its holistic perspective, considering human activity as a dynamic system involving the individual, tools, social structures, and the surrounding context. AT’s multi-layered perspective underscores the collective nature of learning, positioning individuals within a community of practice where learning occurs through collaboration. Its flexibility and applicability across various fields, such as education, psychology, and organizational development, make AT an essential tool for both theoretical analysis and practical application bridging the gap between theory and practice.

Strengths:

- Encourages collaboration and social interaction in learning.

- Applicable in diverse settings such as education, workplaces, and organizations.

- Highlights the role of tools (both physical and abstract) in mediating learning.

One of the primary criticisms is its complexity, as the framework can be difficult to apply, particularly for designers who are used to more straightforward, content-centric learning models. Its focus on a dynamic, contextualized approach to learning requires careful consideration of various elements such as division of labor, community rules, and technology tools, which might overwhelm some practitioners. Additionally, activity theory has faced criticism for its insufficient focus on affect. While the theory addresses cognitive and social dimensions of human activity, it has been less effective in accounting for the emotional and motivational aspects that drive behavior.

Limitations:

- Limited empirical studies show its effectiveness in different contexts.

- Overemphasis on social and cultural contexts might overshadow individual cognitive processes.

- Scaling the theory to large systems or organizations can be challenging.

Instructional Design Implications

Instructors who apply AT typically focus on creating learning experiences that are situated within real-world, goal-oriented activities, where students engage in tasks that involve both cognitive and social interaction. Lessons and activities are designed to reflect the complexity of real-life situations, using tools (both material and abstract) to mediate learning. This approach encourages the integration of collaborative work and critical thinking, with students working together within a community of practice to solve problems and achieve shared goals. Assessments, therefore, focus not just on individual performance but on the students’ ability to work within a system, use tools effectively, and contribute to collective goals.

Specific strategies and tools aligned with AT include collaborative learning activities, problem-based learning (PBL), and the use of authentic tools and artifacts. Instructors can facilitate group projects, discussions, or simulations where students must engage with tools (such as software, documents, or real-world objects) to complete tasks. These tools serve as mediators that shape the cognitive processes of learners. Additionally, AT emphasizes the importance of reflection, so formative assessments such as peer evaluations, self-assessments, and reflective journaling can help students analyze how they used tools and interacted within the activity system.

In different learning contexts, AT can be adapted to design effective learning experiences by focusing on the activity system’s key components: subject, object, tools, community, rules, and division of labor. In traditional classrooms, this might look like group projects where students collaborate to solve problems, using tools like textbooks, software, or research materials. In online learning, instructors can use forums, collaborative digital platforms, or virtual simulations to create social interactions and engage students with mediated tools. For corporate training, AT can inform the design of activities that align with organizational goals, using workplace tools and processes to simulate real-world challenges. By focusing on collaborative, context-rich learning environments, AT helps create dynamic learning experiences that bridge individual knowledge with social and cultural practices across various settings.

Example: Imagine you’re in a high school science class and you’ve been assigned a collaborative research project on climate change. Your goal is to research the effects of climate change in different regions and then present your findings to the class. In this scenario, you (the students) are the subjects of the activity, working together toward the shared goal of understanding and explaining climate change. The object of your activity is to gather and analyze information about climate change, and your tools—like online research platforms, Google Docs, and Google Slides—help you collaborate and organize your data to create a presentation. These tools mediate your learning by making it easier for you to work together, share resources, and put everything into a cohesive presentation.

Now, let’s talk about the community. In this case, the community is made up of your classmates, the teacher, and possibly even outside experts you might interact with. The rules for this project could include things like deadlines for submitting your research, how you divide the work in your group, and expectations for how everyone contributes. Speaking of contribution, this is where the division of labor comes in. Each person in your group might take on a specific task—one person could research the science behind climate change, another could look into the social impact, and someone else might focus on putting the slides together. By dividing the work, everyone contributes to the collective goal of understanding climate change, and that collaboration mirrors how Activity Theory suggests learning happens—through interaction, social participation, and the use of tools to help achieve shared objectives.

Conclusion

Activity Theory contributes to the understanding of learning by emphasizing it as a social process that occurs through purposeful interaction within a community, using tools to mediate the relationship between consciousness and activity. This approach shifts focus away from individual-oriented learning theories and highlights the importance of social context and collaboration in cognitive development. AT emphasizes that learning is shaped by shared activities within cultural and social contexts, where both material and abstract tools play a crucial role in facilitating learning. This perspective provides deeper insights into how individuals and groups develop through their interaction with tools, their community, and the activity systems they participate in.

The broader implications of AT for education, instructional design, and psychological research are significant. For educators, AT encourages the creation of learning environments rich in social interaction and reflective of real-world activities, where students engage with tools and collaborate to achieve meaningful goals. Emerging technologies, such as collaborative online workspaces and virtual simulations, can further enhance AT by providing new tools for social learning and real-world task engagement. While AT remains highly influential, it is not without limitations, such as the under-researched empirical evidence and the need for more consideration of power dynamics in activity systems. Despite these challenges, AT continues to offer valuable insights into learning processes and can be adapted to various educational and organizational contexts.

Review what you’ve learned

Licenses and Attribution

“Activity Theory” by Lisa Costa is adapted from “Theories of Learning” by AIU courses, “Leontyev’s activity theory and social theory – ethical politics” by A. Bluden, “Activity theory as a lens for developing and applying personas and scenarios in learning experience design” by M. Schmidt and A. Tawfik licensed under CC BY 4.0., “Activity system diagram” by M. Bury “Activity theory”, and “Aleksei Leontiev” from Wikimedia licensed under CC BY-SA, “Activity Theory” is licensed under CC BY-SA.