Jerome Bruner and Constructivist Learning Theory

Kimberly Tomkinson

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Identify how Bruner’s three modes of representation influence the way learners process and store knowledge.

- Compare Bruner’s ideas about constructivism and learning to those of other theories.

- Recognize Bruner’s concept of scaffolding as it applies to classroom instruction.

Introduction to Bruner

Overview

Jerome Bruner (1915-2016) was a cognitive psychologist and education theorist and is known for his contributions to constructivist learning theory. His work helped to shape modern educational psychology by focusing on how learners play an active role in constructing knowledge, instead of passively absorbing information. Bruner believed that learning is an ongoing process where individuals build their learning by adding to their previous knowledge as they interact with new concepts and refine and expand their understanding over time (Bruner, 1966).

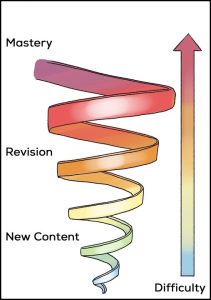

Bruner’s Spiral Curriculum is an important part of his work. It proposes that learners revisit topics at increasing levels of complexity and abstraction. This approach helps learners deepen their understanding in a progressive way, as opposed to being introduced to concepts only once. This idea is often represented visually as a spiral, illustrating how learners return to key concepts with increasing depth and complexity. The image below demonstrates how topics are revisited over time, building on prior knowledge to promote deeper understanding.

Figure 1: Spiral Curriculum. Spiral representing learning progression with labels “New Content,” “Revision,” and “Mastery,” and an arrow showing increasing difficulty.

Bruner also introduced three modes of representation that describe how learners process and store knowledge:

- Enactive Representation: Learning through physical action and direct experience.

- Iconic Representation: Learning through visual images and mental models.

- Symbolic Representation: Learning through language, symbols and abstract thinking (Bruner, 1964).

His theories have had a significant and lasting impact on educational practices, especially in areas of curriculum design, discovery learning, and scaffolding.

Importance

Bruner’s work is relevant to the way students learn in environments that are student-centered and inquiry-based. His ideas support problem-based learning, project-based learning, and experiential learning approaches.

His emphasis on scaffolding, where teachers provide temporary support to help students move from lower to higher-order thinking, has influenced instructional design and differentiated learning approaches (Wood, Bruner, & Ross, 1976). Additionally, his theories contribute to advancements in educational technology, particularly in adaptive learning environments and AI-driven personalized instruction (Mayer, 2008). The intersection of Bruner’s ideas with modern learning technologies shows that his constructivist approach is still shaping the digital learning landscape.

Biographical Context

Early Life and Education

Jerome Bruner was born in New York City in 1915. He was born blind, but at the age of two, had corrective surgery that allowed him to see and develop normally. His early academic career happened during the Great Depression, which was a time when issues in society sparked his interest in psychology and human development.

Bruner earned a bachelor’s degree in psychology from Duke University in 1937 and later earned a Ph.D. in psychology from Harvard University in 1941. He was influenced by the behaviorist movement during his studies, but aligned more with cognitive psychology, attracted by the work of Jean Piaget and Lev Vygotsky (Smith, 2002).

Career Highlights

Bruner worked for several decades and his contributions to the fields of psychology and education are still important today. Some key aspects include:

- 1940’s-1950’s: Established himself as a leader in cognitive psychology, challenging dominant behaviorist theories.

- 1960: Introduced Spiral Curriculum concept in The Process of Education.

- 1970’s-1980’s: Focused on cultural and narrative psychology that emphasized storytelling in learning.

- 1990’s-2000s: Continued to influence educational reform and constructivist practices throughout the world (Bruner, 1996).

Bruner’s work helped to lay the foundation for modern theories of constructivist learning, scaffolding, and inquiry-based instruction.

Theoretical Contributions

Core Concepts

Bruner’s theory of constructivist learning is based on the idea that learners actively construct their own understanding. He thought education should focus on discovery learning, where students are encouraged to explore and solve problems. He also emphasized Spiral Curriculum, where concepts are revisited with increasing depth over time, as well as scaffolding, where instructors give structured support to help learners develop their own problem-solving skills (Bruner, 1978).

Some examples of these concepts can help illustrate how they can be used in the classroom.

Inquiry-Based Learning

In a high school biology class, for example, students investigate ecosystems. The teacher starts the unit by presenting students with the question: “why do some species thrive and others struggle in a given environment?” Instead of giving students the answers, the teacher puts students into groups and gives them data sets on local ecosystems, climate conditions, and species populations. Students are asked to form hypotheses, analyze the data, and design experiments to test factors that affect biodiversity. The teacher provides scaffolding by guiding the discussions and offering resources when it is apparent that students need additional support. At the end of the unit, students present their findings and compare their conclusions to scientific studies.

This method encourages critical thinking, collaboration, and real-world problem solving, which all align with Bruner’s belief that students should actively construct knowledge, instead of passively receiving it.

Discovery Learning

Discovery learning encourages students to find solutions to problems using exploration, prior to students receiving instruction directly. For example, in a geometry class, instead of starting with a lecture on the Pythagorean Theorem, students are given a set of right triangles and are asked to measure the sides of the triangles, record the measurements, and then look for patterns in the relationships between the squares of the sides. Students discover the consistent pattern that a² + b² = c² before the teacher introduces the theorem. This approach is more meaningful and memorable for students because they are actively engaging in the problem-solving process instead of being given a formula to memorize.

Spiral Curriculum

The concept of Spiral Curriculum is that students will revisit key concepts during their education, building upon them with increasing depth and complexity. For example, in a high school history class students are introduced to the concept of civil rights in the 9th grade as they discuss historical events in the U.S. Then in 10th grade, they revisit the topic when they study world history and compare global civil rights movements, like apartheid in South Africa and the suffrage movement in the UK. In 11th grade, students return to civil rights discussions in American Government class and analyze legislation, Supreme Court cases, and political activism. Finally, in 12th grade, students integrate all they have learned previously about civil rights in a project where they research and present on current human rights issues and propose policy recommendations.

By applying Bruner’s ideas in classrooms, educators create engaging, student-centered, learning experiences that encourage active participation, deeper understanding, and real-world application of knowledge.

Notable Works

Bruner’s most influential works include:

- The Process of Education (1960) where he introduced the concept of Spiral Curriculum.

- Toward a Theory of Instruction (1966) where he expanded on discovery learning and cognitive development.

- Acts of Meaning (1990) where he explained the role of narrative and culture in learning.

Note: His later work in Acts of Meaning (1990) underscores how cultural contexts shape cognition and learning, an aspect that is particularly relevant in multicultural education today.

Supporting Mechanisms

Bruner’s ideas are supported by different mechanisms that facilitate learning and cognitive development. One of the most significant is scaffolding, discussed by Wood, Bruner, and Ross (1976). It refers to temporary support that instructors give to students, which helps them develop their skills and understanding. As students become more proficient, the support is gradually removed and they become more independent in their learning process. Another important mechanism is problem-solving and inquiry-based learning. These strategies emphasize exploring as opposed to memorizing. Instead of just absorbing information, students engage in active problem-solving, ask questions, and discover concepts through their experiences. Bruner also discussed how social and cultural contexts influence learning (Bruner, 1966). He believed that interactions with peers, educators, and a student’s cultural environment helped to shape their cognitive development. These mechanisms support Bruner’s constructivist approach and help learning be dynamic and interactive, as well as within meaningful contexts.

Comparison with Other Theorists

Similarities

Jerome Bruner’s theories have some similarities to those of Jean Piaget and Lev Vygotsky. Like Piaget, Bruner believed learners should be active participants in their own learning, constructing their own understanding, as opposed to being passive recipients of information. In addition, both Bruner and Piaget promoted the belief that cognitive development plays an important role in how individuals acquire and apply knowledge. Along with Vygotsky, Bruner also recognized that social interaction and scaffolding are important parts of learning.

Differences

Bruner differed in some of his theories when compared to those of Piaget and Vygotsky, however. Piaget believed that learners move through specific developmental stages and in contrast, Bruner saw learning as a continuous spiral where concepts are revisited at increasing levels of complexity over time. With social learning, both Bruner and Vygotsky thought it was important, but Bruner emphasized discovery-based and inquiry-based learning. He believed students should be encouraged to explore and construct knowledge through active problem-solving.

Strengths & Limitations

Strengths

Bruner’s work has had a lasting impact on education and a significant aspect is that his ideas pair well with modern educational technologies. In addition, his emphasis on active, inquiry-based learning encourages critical thinking as learners explore, question, and discover knowledge. He also made scaffolding an integral part of the learning process, giving support to learners as the teacher guides a student, providing necessary assistance until they can work independently.

Limitations

Bruner’s ideas are not without limitations, however. Some believe that his work doesn’t emphasize individual cognitive differences enough and instead assumes all learners can go through discovery-based learning in the same way. His Spiral Curriculum and inquiry-based learning ideas are effective in several settings, but can be difficult to implement in standardized educational systems. These settings may limit opportunities for student-driven exploration and therefore a balanced approach is recommended when applying Bruner’s ideas in educational contexts.

Implications for Education

Instructional Design

Bruner’s ideas have been influential in how curriculum development, lesson planning, and differentiated instruction have evolved over the past several decades. His Spiral Curriculum has helped educators understand the need to introduce foundational concepts early and then revisit them in increasing levels of complexity. This allows learners to gain a deeper understanding of concepts over time. Bruner emphasized discovery learning, which has helped educators move towards a more student-centered, inquiry-based model of instruction. These approaches allow learners to explore as they learn and use hands-on activities and problem-based approaches, instead of memorizing facts and details. Finally, his work using scaffolding has encouraged teachers to provide structured support to learners and then gradually remove it as learners become more proficient. The principles Bruner proposed are used in modern teaching strategies, especially in project-based learning, collaborative group work, and differentiated instruction. This helps engage learners in their knowledge acquisition and allows educators to adapt instruction to meet diverse learner needs.

Application of Bruner’s Ideas in Instructional Design

Bruner’s theories aren’t just abstract concepts—they have real, practical applications in classrooms, especially in hands-on learning environments. An example of this is a college-level construction course, where students learn framing principles using a mix of discovery learning, scaffolding, and problem-solving. Instead of simply lecturing, the instructor, Mr. Reynolds, designs activities that encourage students to figure things out for themselves while still providing structured support when needed.

Case Study: Learning Framing Through Scaffolding and Discovery

Getting Started: Exploring Before Explaining

Instead of diving straight into blueprints and measurements, Introduction to Construction instructor, Mr. Reynolds, kicks things off with a simple but thought-provoking activity. He sets up several wall frames—some built correctly and others with obvious flaws—and asks students:

- Which frame looks the strongest? Why?

- What do you think happens if studs aren’t spaced properly?

Students test their ideas by applying force to the frames, experiencing firsthand what happens when a structure isn’t built correctly. Only after this discovery process does Mr. Reynolds introduce blueprints and technical specifications, allowing students to compare what they assumed with how framing actually works in professional construction.

Hands-On Learning: Building with Guidance

With their foundational knowledge in place, students move on to building partial wall sections in teams. At first, Mr. Reynolds provides step-by-step demonstrations on:

- Measuring and marking stud placements

- Aligning and securing headers and sills

- Making sure the frame is structurally sound

As students start assembling their walls, his teaching style shifts—instead of giving answers, he starts asking questions:

- “What do you need to check before securing that header?”

- “How can you make sure this frame will hold weight properly?”

This gradual pulling back of support is what Bruner called scaffolding—helping students gain confidence so they can eventually work independently.

Problem-Solving: Learning from Mistakes

As students take on larger, more complex projects, they run into real-world problems, just like they would on a job site:

- Some misplace their studs → They have to measure diagonally to fix alignment.

- Some hammer nails too deep → They adjust pressure for better stability.

- Some frames don’t distribute weight evenly → They reinforce weak spots.

Instead of stepping in to fix their mistakes, Mr. Reynolds challenges them to troubleshoot. When a team struggles, he asks:

- “What’s your next step to correct this?”

- “How would a professional builder approach this problem?”

By working through these challenges, students develop problem-solving skills that go far beyond just framing walls.

Relevance in Modern Education

Bruner’s ideas are still helping to shape the way education happens today. His influence is especially notable where critical thinking, problem-solving, and student engagement are emphasized. In STEM education, where inquiry-based learning is widely used, Bruner’s work has had a significant impact. In addition, the ever-increasing use of educational technologies has helped to reinforce Bruner’s ideas, encouraging personalized learning pathways for learners through the use of AI-driven platforms with scaffolding techniques. Student-centered learning environments are supported by Bruner’s contributions and movement away from the traditional, lecture-based model of instruction is ever-increasing. His ideas will continue to be a significant influence on learning and teaching as technologies emerge and new learning models are created.

Conclusion

Jerome Bruner and his constructivist learning theory have helped shape educational psychology, instructional design and curriculum design in significant ways. His Spiral Curriculum, discovery learning and scaffolding ideas are used in teaching all over the world and his legacy is felt in classrooms across the globe. His contributions will keep shaping the way learners engage with knowledge and how educators and designers craft instruction in this modern technological world in which individuals live and learn.

Reflection

Bruner’s theories help us understand how people learn through actions, images, and language. In this activity, you will test your knowledge of his key ideas, including modes of representation, constructivist learning, and scaffolding.

Instructions:

- Drag the correct words into the blanks to complete the sentences.

- If you get an answer wrong, read the feedback to help you learn.

- Try again until you get all the answers correct!

References

Bruner, J. S. (1960). The process of education. Harvard University Press.

Bruner, J. S. (1966). Toward a theory of instruction. Harvard University Press.

Bruner, J. S. (1978). The role of dialogue in language acquisition. Cambridge University Press.

Mayer, R. E. (2008). Applying the science of learning: Evidence-based principles for the design of multimedia instruction. American Psychologist, 63(8), 760–769.

Smith, M. K. (2002). Jerome S. Bruner and the process of education. Infed.org. Retrieved from https://infed.org/mobi/jerome-bruner-and-the-process-of-education.

Wood, D., Bruner, J. S., & Ross, G. (1976). The role of tutoring in problem-solving. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 17(2), 89–100.

Licenses and Attribution

“Jerome Bruner” by Kimberly Tomkinson is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Spiral Curriculum” by Gagandeep Kur is used from OER Commons, licensed under CC BY 4.0.

AI Attribution:This work was primarily created by a human author. AI (ChatGPT 4.0) was used to assist with stylistic editing, including improvements to structure, wording, and clarity. All AI-generated suggestions were prompted intentionally and reviewed and approved by the author.