Gagne’s 9 Events of Instruction

Nicholas Lambertsen

Learning Objectives

Type your learning objectives here.

- Identify fundamental tenets of Gagne’s 9 events of instruction

- Identify design processes associated with Gagne’s 9 events of instruction

Introduction to Learning Theory

Gagne’s Nine Events of Instruction is an instructional design model that connects directly with his learning theory, “Conditions of Learning.” Gagne suggested that not all learning is equal and that each learning domain should be presented and assessed differently. Therefore, as an instructional designer, one of the first tasks is determining which learning domain applies to the content. Gagne also theorized an effective learning process consisting of nine distinct steps. Each step corresponds to a process in the brain that Gagne identified as necessary for effective learning to occur. These nine events are: gaining attention, informing the learner of the objective, stimulating recall of prior learning, presenting the stimulus, providing learner guidance, eliciting performance, providing feedback, assessing performance, and enhancing retrieval and transfer. These events build naturally upon each other and improve the communication supporting the learning process. This sequence provides a framework from which educators can organize information that allows for effective and efficient learning.

The impact Robert Gagne had on the field of instructional design is substantial. For example, we can trace the evolution of the domains of learning from the Conditions of Learning through other theories such as Merrill’s Component Display Theory (1994), to Smith and Ragan’s Instructional Design Theory (1992), to van Merrienboer’s complex cognitive skills in the 4C/ID model of instructional design (1997). Beyond that, Gagne’s Nine Events of Instruction also paved the way for a systematic process for designing instruction. For the first time, those designing instruction had a blueprint to follow. Almost 60 years later, Gagne’s work still serves as the basic framework all instructional designers.

Origins of the Learning Theory

As the United States entered World War II, it faced an enormous problem: How would it train so many troops? The military trained over 16 million soldiers. The technology of the war had changed drastically from World War I, and troops needed training on all the skills necessary to operate. Training needed to be done quickly, effectively, and efficiently.

After the war ended, cognitive psychologists, many of whom had served in World War II, began studying how to apply the training lessons from the war to other instructional settings to help people learn better. Combining the work of those researchers, the systematic instructional design process was born.

Robert Gagne was working on his Ph.D. in Psychology when World War II began. While assigned to Psychological Research Unit No. 1, he administered scoring and aptitude tests to aviation cadets. After the War, Gagne joined the Air Force Personnel and Training Research Center where he directed the Perceptual and Motor Skills Laboratory. His experiences and training in the military guided much of his research. In 1959, he participated in the prestigious Woods Hole Conference, a gathering of outstanding educators, psychologists, mathematicians, and other scientists from the United States in response to the Soviet Union launching the Sputnik satellite. Results of the conference were published in Bruner’s The Process of Education (1961). Four years later, Gagne published The Conditions of Learning (1965). Instructional design was born out of his and others’ theories.

Gagne studied behaviorism, which is reflected in his early works; however, as the field of psychology shifted, so did Gagne’s views. According to Kretchmar (2015), Gagne was among the first theorists to stop seeking a one-size-fits-all description of student learning and suggest that people learn in diverse ways. Moving away from behaviorism, his later work “was influenced by the information processing view of learning and memory” (Dempsey, 2002, p.365), which is demonstrated in his learning theory.

Fundamental Tenets

Gagne proposed that effective learning depends on what happens in the brain as well as the conditions of the learning environment. Internal conditions occur in the brain and constitute the learner’s knowledge of the subject based on previous experiences. This can change depending on what kind of skill is being learned. According to his theory, there are nine processes that occur in the brain necessary for learning. The corresponding conditions of the learning environment are listed as nine events of instruction. These events help connect how people learn with how teachers should teach.

An explanation of the conditions of learning can be found in the video below.

As stated above, each of the nine events corresponds to an internal cognitive process that Gagne identified as necessary for effective learning to take place. These events are listed in the table below.

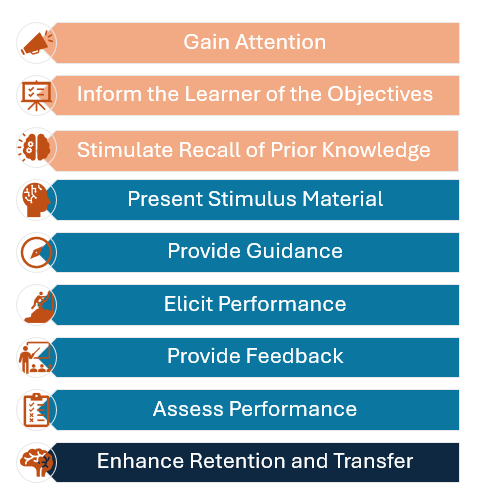

The image illustrates “Gagne’s 9 Events of Instruction” as a flow chart composed of colored horizontal bars aligned vertically. Each event is accompanied by an icon symbolizing its function. The chart is divided into three phases, each represented by a specific color. The Preparatory Phase (items 1 to 3) is in light orange, including “1. Gain Attention,” “2. Inform Learners of Objectives,” and “3. Stimulate Recall of Prior Knowledge.” The Acquire and Practice New Knowledge Phase (items 4 to 8) is in blue, featuring “4. Present the Stimulus Material,” “5. Provide Learner Guidance,” “6. Elicit Performance,” “7. Provide Feedback,” and “8. Assess Performance.” The Further Application of Skills and Content Phase (item 9) is in dark blue, consisting of “9. Enhance Retention and Transfer.” Each phase is represented by a corresponding legend in the bottom right corner.

The first three events of this model make up the preparatory stage. To learn, students need to be open to learning (attentive), understand what they are going to learn, and think about what they already know. This aligns with Gagne’s belief that learning needs to happen in steps to continuously build concepts from simple to more complex as the learning develops. It also supports the idea that learning is better retained when students can make meaningful connections with the new material.

Preparatory Phase

Event one: Gain attention.

Before learning can happen, learners must be engaged. To gain the learners’ attention, any number of strategies can be employed. It could be as simple as turning the lights on and off, the teacher counting down, or the teacher clapping three times.

Event two: Inform learners of objective.

Once learners are engaged, they are informed of the objective of the instruction, which gives learners a road map to the instruction. It allows them to actively navigate the instruction and know where they are supposed to end up.

Event three: Stimulate recall of prior knowledge.

Stimulating recall of prior learning allows learners to build upon previous content covered or skills acquired. This can be done by referring to previous instruction, using polls to determine previous content understanding (and then discussing the results), or by using a discussion on previous topics as a segue between previous content and new content.

During the next five events, students learn and practice new knowledge or skills. The new knowledge or skill is presented or demonstrated depending on the type of learning is happening. Remember the five domains discussed in the video. When instructors provide learner guidance, they show them how to do the skill and how to connect it to what they already know, which helps them retain the information. Eliciting performance allows students to practice the new skill in a low-risk setting; mistakes are acceptable and should be followed by feedback. After receiving feedback, what students learned can be assessed, and then they should receive additional feedback from the instructor.

Acquisition and Practice of New Knowledge Phase

Event four: Present the stimulus material.

Presenting the stimulus material is simply where the instructor presents new content. According to Gagne, this presentation should vary depending on the domain of learning corresponding to the new content.

Event five: Provide learner guidance.

Providing learner guidance entails giving learners the scaffolding and tools needed to be successful in the learning context. Instructors can provide detailed rubrics or give clear instruction on expectations for the learning context and the timeline for completion.

Event six: Elicit performance.

Eliciting performance allows learners to apply the knowledge or skills learned before being formally assessed. It allows learners to practice without penalty and receive further instruction, remediation, or clarification needed to be successful.

Event seven: Provide feedback.

In conjunction with eliciting performance in a practice setting, the instructor provides feedback to further assist learners’ content or skill mastery.

Event eight: Assess performance.

Following the opportunity to practice the new knowledge or skill (events five, six, and seven), learner performance is assessed. The performance must be assessed in a manner consistent with its domain of learning. For example, verbal knowledge can be assessed using traditional fact tests or with rote memorization, but motor skills must be assessed by having the learner demonstrate the skill.

Finally, Gagne suggests that learning should not happen in just once. It should continue and build up over time. The last step ensures learners use what they have learned in new and different situations and opportunities, such as occasional reviews to practice recall. This should help students retain information and use what they have learned in the future.

Event nine: Enhance retention and transfer.

Enhancing retention and transfer gives the learner the opportunity to apply the skill or knowledge to a previously unencountered situation or to personal contexts. For example, using class discussion, designing projects, or by writing essays.

Strengths and Limitations

The following section was adapted from a response generated by ChatGPT (OpenAI, 2025):

The strength of Gagne’s theory is in its clear structure. It provides instructors a step-by-step plan that any educator can apply to their unique circumstance. This model ensures that students are prepared to learn, receive the guidance they need, practice their skills in low-risk situations, and receive helpful feedback. It also ensures that instructors assess their skills and provides multiple opportunities to remember and apply those skills in new situations. Additionally, Gagne’s approach is particularly helpful in environments where clear, step-by-step instruction are necessary, such as job training, military instruction, or classes that teach hands-on skills.

One downside of this model is that students need a lot of guidance to learn new skills. According to Gagne, each of the nine events must be followed for effective learning to occur. The degree of support required of the instructor could lead to one or more of the events being ignored or missed. This dependency on structured guidance makes the model less effective in classroom environments where students guide their own learning, such as project-based learning, where students explore concepts independently. Additionally, these steps may be overly simple when learning is more complex, like open-ended problem-solving or critical thinking development. A rigid structure like this model may not fit with how people learn in real-world situations.

Implementation in Instructional Design

Implementing Gagne’s Nine Events of Instruction is quite simple. The instructor follows the given framework and designs activities related to each step. The following describes each event in the context of the three previously mentioned phases. Each event is accompanied by a few practical applications and how each event is applied to a specific scenario focused on teaching knee anatomy, injuries, and examination. The following learning objectives are given in that teaching scenario:

- Identify anatomical structures of the knee.

- Name the most common injuries of the knee and their specific mechanism of injury.

- Perform a complete exam of the knee.

The specific instructional examples in the following section were adapted from a response generated by ChatGPT (OpenAI, 2025)

Preparatory Phase:

Gain Attention

These are a few methods for capturing learners’ attention:

- Stimulate students with novelty, uncertainty, and surprise

- Pose thought-provoking questions to students

- Have students pose questions to be answered by other students

- Lead an ice breaker activity

Gaining Attention in Practice

Inform the Learner of Objectives

Here are some methods for stating the outcomes:

- Describe required performance

- Describe criteria for standard performance

- Have learners establish criteria for standard performance

- Include course objectives on assessment prompts

Informing the Learner of Objectives in Practice

Stimulate Recall of Prior Learning

There are numerous methods for stimulating recall.

- Ask questions about previous experiences

- Ask students about their understanding of previous concepts

- Relate previous course information to the current topic

- Have students incorporate prior learning into current activities

Stimulating Recall of Prior Knowledge in Practice

Acquire and Practice New Knowledge Phase

Present the Stimulus Material

The following are ways to present and cue lesson content:

- Present multiple versions of the same content (e.g. video, demonstration, lecture, podcast, group work, etc.)

- Use a variety of media to engage students in learning

- Incorporate active learning strategies to keep students involved

- Provide access to content on Blackboard so students can access it outside of class

Presenting the Stimulus Material in Practice

- Anatomy: The instructor uses a knee model, allowing students to explore the bones, ligaments, and muscles in detail. Additionally, a live model is used to identify each anatomical structure.

- Injuries: Case studies of actual knee injuries are presented, detailing mechanisms such as ACL tears from sudden deceleration and MCL injuries from lateral impact.

- Examination: The instructor demonstrates a step-by-step knee examination using a volunteer, explaining each test’s purpose and expected findings

Provide Learner Guidance

The following are examples of methods for providing learning guidance:

- Provide instructional support as needed – i.e. scaffolding that can be removed slowly as the student learns and masters the task or content

- Model varied learning strategies – e.g. mnemonics, concept mapping, role playing, visualizing

- Use examples and non-examples – examples help students see what to do, while non-examples help students see what not to do

Provide case studies, visual images, analogies, and metaphors – Case studies provide real world application, visual images assist in making visual associations, and analogies and metaphors use familiar content to help students connect with new concepts.

Providing Learner Guidance in Practice

Elicit Performance

Here are a few ways to activate learner processing:

- Facilitate student activities – e.g. ask deep-learning questions, have students collaborate with their peers, facilitate practical laboratory exercises

- Provide formative assessment opportunities – e.g. written assignments, individual or group projects, presentations

- Design effective quizzes and tests – i.e. test students in ways that allow them to demonstrate their comprehension and application of course concepts (as opposed to simply memorization and recall)

Eliciting Performance in Practice

Provide Feedback

The following are some types of feedback you may provide to students:

- Confirmatory feedback informs the student that they did what they were supposed to do. This type of feedback does not tell the student what she needs to improve, but it encourages the learner.

- Evaluative feedback apprises the student of the accuracy of their performance or response but does not provide guidance on how to progress.

- Remedial feedback directs students to find the correct answer but does not provide the correct answer.

- Descriptive or analytic feedback provides the student with suggestions, directives, and information to help them improve their performance.

- Peer-evaluation and self-evaluation help learners identify learning gaps and performance shortcomings in their own and peers’ work

Providing Feedback in Practice

Assess Performance

Some methods for testing learning include the following:

- Administer pre- and post-tests to check for progression of competency in content or skills

- Embed formative assessment opportunities throughout instruction using oral questioning, short active learning activities, or quizzes

- Implement a variety of assessment methods to provide students with multiple opportunities to demonstrate proficiency

- Craft objective, effective rubrics to assess written assignments, projects, or presentations.

Further Application of Skills and Content Phase

Enhance Retention and Transfer

The following are methods to help learners internalize new knowledge:

- Avoid isolating course content. Associate course concepts with prior (and future) concepts and build upon prior (and preview future) learning to reinforce connections.

- Continually incorporate questions from previous tests in subsequent examinations to reinforce course information.

- Have students convert information learned in one format into another format (e.g. verbal or visuospatial). For instance, requiring students to create a concept map to represent connections between ideas (Halpern & Hakel, 2003, p. 39).

- To promote deep learning, clearly articulate your lesson goals, use your specific goals to guide your instructional design, and align learning activities to lesson goals (Halpern & Hakel, 2003, p. 41).

Enhancing Retention and Transfer in Practice

Conclusion

Gagné’s Nine Events of Instruction provide a clear framework for designing effective learning experiences by considering how the brain processes information and the conditions of the learning environment. This model ensures that learners are engaged, guided, and supported throughout the learning process, making it highly applicable to various educational settings.

The following section was adapted from a response generated by ChatGPT (OpenAI, 2025):

Gagné’s theory doesn’t just help instructors plan lessons, it also influences how schools create their programs, train teachers, and teach people in the workplace. His step-by-step approach helps students remember what they learn and build useful skills. Gagné’s ideas have also brought together two ways of thinking about learning: behaviorist and cognitive perspectives, demonstrating that learning is both an observable behavior and an internal cognitive process.

His work has helped psychological researchers understand more about learning. For example, his ideas have helped explain why things like practice, feedback, and support help improve learning. Studies on cognitive load, multimedia learning, and adaptive instruction have built upon his principles, reinforcing the importance of structured learning environments.

As learning keeps changing, Gagné’s model is still useful. It gives teachers and lesson designers a proven way to help students succeed.

References

Dempsey, J. V. (2002). Robert M. Gagne. British Journal of Educational Technology, 33, 365–366. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8535.00273

Halpern, D. F., & Hakel, M. D. (2003). Applying the science of learning to the university and beyond: Teaching for long-term retention and transfer. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 35: 36-41. https://seaver-faculty.pepperdine.edu/thompson/projects/wasc/Applying%20the%20science%20of%20learning.pdf

Kretchmar, J. (2015). Gagné’s Conditions of Learning. Research Starters: Education (Online Edition).

OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT (Feb 22 version) [Large language model]. OpenAI. https://chat.openai.com/

Licenses and Attributions

“Gagne’s Nine Events of Instruction” by Nick Lambertsen is adapted from the following sources:

- “Robert Gagné in the 21st century: Behind the conditions of learning and the nine events of instruction” by Aimee Lambertz, used under a CC BY 3.0 License

- “Robert Gagné and the Systematic Design of Instruction. Design for Learning: Principles, Processes, and Praxis” by John Curry, used under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License

- “Gagné’s nine events of instruction. In Instructional guide for university faculty and teaching assistants” by Northern Illinois University Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning, used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 License.

“Gagne’s Nine Events of Instruction” by Nick Lambertsen is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA.

AI Attribution: AIA Primarily human, Content edits, New content, Human-initiated, Reviewed, ChatGPT v1.0