13 Lesson 13: Syntax–How do languages organize phrases and sentences? (complete lesson–pending self-check questions)

Syntax: How do languages organize phrases and Sentences?

About Word Order

Sentences throughout the world’s languages contain three basic parts (constituents):

- A subject: the doer of the action or experiencer of the state of being

- A verb: the action or state of being

- An object: the receiver of the action

Objects can take two forms: direct and indirect. A direct object receives the action. An indirect object (often preceded by a preposition in English) receives the direct object.

An example sentence in English with a direct object and an indirect object (a di-transitive sentence) is:

Alex gave the book to Sacha.

In this example, ‘Alex’ is the subject, ‘gave’ is the verb, ‘book’ is the direct object, and ‘Sacha’ is the indirect object.

These three basic parts–subject, object, and verb–can occur in a variety of orders throughout the world’s languages. Each language, though, usually has a preferred or ‘basic’ word order. In the English example sentence above, you can see that the word order (which really could be called ‘constituent order’) is Subject-Verb-Object (or SVO). Other languages, though, can have SOV, VSO, OVS, or any other word order, depending on how their language does it. Some languages have ‘free’ word order, meaning that in those languages, the constituents can occur in any order. In free word order languages, though, there are usually other ways to indicate which part of the sentence is the subject or the object.

About the Nested Nature of Language

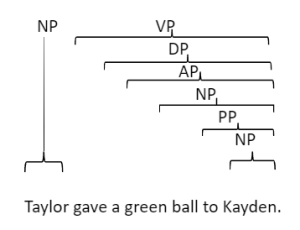

Sentences in human language are built out of these main constituents, grouped into phrases. We describe these phrases in terms of which part of the phrase is the ‘head’ of the phrase. Verb phrases have ‘verbs’ as their heads. Noun phrases have ‘noun’s as their heads, or are ‘governed by’ the noun.

These phrases are nested, so that smaller phrases can occur inside of larger phrases.

For example, in the English sentence below, you can see that there are several phrases inside the verb phrase. The verb phrase and its object(s) in English is called the ‘predicate’. Remember, though, that not all languages work this way.

About Headedness

The headedness parameter is used to explain sentence structure variations among the world’s languages. Some languages are head-first and some area head-last. English is a head-mixed language with a head-first verb structure. This means that the ‘head’ of the phrase comes first. The head of a verb phrase is the verb. In our example sentence, the head of the verb phrase is ‘gave’ and it comes at the beginning of the phrase ‘gave a green ball to Kayden’.

In our example sentence, the phrases are nested and labeled in a way to indicate full head-first structure. There is some argument, however, as to whether the noun phrase in English is head last, as the adjectives and determiners come first. Some linguists argue that the noun is the head of the noun phrase, which entails all adjectives and determiners, in English. Others, however, argue that the structure I have listed above is more accurate, with a determiner as head of a determiner phrase, containing an adjective phrase, with an adjective as the head, and then a noun. I am not going to solve this issue. Linguists like to argue.

In this sentence from Korean, though, from Lehman (2004), the head of the phrase is last, not first.

Toli-n🡪n kae-hako cal non-ta.

Toli-TOP dog-ADD often/well play:PRS-DECL

| Toli-n🡪n | kae-hako | cal | non-ta. |

| Toli-TOP | dog-ADD | often/well | play:PRS-DECL |

‘Toli likes to play with the dog.’

The verb ‘play’ (including the suffixed morpheme DECL, meaning ‘declarative mood’) is the last element of the verb phrase. In Korean, a Subject-Object-Verb (SOV) language, the object comes before the verb. This makes Korean a head-last language. Similarly, Choctaw is a head last language for verb structure.

Issi tohbi chito pisa.

3s ‘deer’ ‘white’ ‘big’ ‘see’.

| Issi | tohbi | chito | pisa. | |

| 3s | ‘deer’ | ‘white’ | ‘big’ | ‘see’. |

‘She sees a big white deer.’

In the Choctaw sentence ‘She sees a deer’, the verb pisa, ‘to see’, is at the end of the verb phrase ‘sees a deer’. Like Korean, Choctaw is a Subject Object Verb (SOV) language. Most languages with a word order where the object comes before the verb are considered head-last. In Choctaw, though, the noun phrase also appears to be head-first! It is mixed like English, but with the opposite headedness settings.

Many languages have mixed headedness (Cinque 2017). Rigid fixed headedness is relatively uncommon. Remember, though, English is not the ‘normal’ setting for language any more than any other language. In fact, John McWhorter, who hosted the linguistics podcast Lexicon Valley argues that English is downright weird compared to most languages.

Activity! Determining Word Order and Headedness

Purpose:

- To practice identifying word order from real-world language examples.

- To practice identifying headedness in verb phrase structure.

- To practice decoding interlinear glosses.

Instructions:

- Using the following data, try to identify the constituent order (word order) and headedness of the verb phrase.

- Remember that you don’t have to understand every grammatical abbreviation (the parts in all caps) to be able to decode these interlinear glosses. You are looking for clear parts of speech like nouns, verbs, and adjectives.

- The data are taken from Cinque (2017). The names of the languages for each sentence has been intentionally omitted.

The Data:

Set 1.

| Watasi-wa | [kare-ga | osoraku | sore-o | zyoozuni | okona-e-ru | to] | it-ta. |

| I-TOP | [he-NOM | probably | it-ACC | well | do-MOD-PRES | COMP] | say-PAST |

‘I said that probably he can do it well’

Set 2.

| Tyi | k-sub-u | [che` | mi | i-bajb-eñ | ts’i` | aj-Wãn]. |

| PRFV | A1-say-TV | COMP | IMPF | A3-hit-DEM.NML | dog | CL-Juan |

‘I said that Juan hits the dog.’

Set 3.

| a | ɗá-r | kərá=j | nə | dʒíf | Lawu |

| PFV | hit-EXT | dog=REL | with | stick | Lawu |

‘Lawu hit the dog with the stick.’

Set 4.

| yer | ngeti | tyapat | me | tu |

| tomorrow | I(1s) | sit.swim | PROG | FUT |

‘Tomorrow I shall be swimming’

Set 5.

| yisi | Tolstoy-ä | cäx-ru(-ni) | łena | y-exora | t’ek |

| DEM | Tolstoy-ERG | write-PST.PTCP-DEF | five | II-long | book.ABS.II |

‘these five long books written by Tolstoy’

Set 6.

| Nunqan | ulle-ve | tulile | lo:van-d’e-ngne-re-n |

| She | meat-ACC | outdoors | hang-IMPRF-HAB-PAST-AGR |

‘She usually hangs meat outdoors for some time (for drying)’

Set 7.

| Na‘e | kamata | [langa | ‘e | Sione | ‘a | e | ngaahi | fale]. |

| PAST | begin | build | ERG | (name) | ABS | DEM | PL | house |

‘Sione began building the houses.’

References

Chomsky, N. (1981). Lectures on Government and Binding. Foris.

Cinque, G. (2017). A microparametric approach to the head-initial/head-final parameter. Linguistic Analysis, 41(3-4), 309-366.

Lehman, C. (2004). Interlinear morphemic glossing. In Morphologie. Ein internationals Handbuch zur Flexion und Wortbuilding. 2. Halbband. Walter De Gruyter, pp. 1834-1857.

McWhorter, J. (March 30, 2021). English is Plain Weird. Lexicon Valley. Slate. https://slate.com/podcasts/lexicon-valley/2021/03/english-language-not-normal