Chapter 4 Measuring Geological Time

Originally fossils only provided us with relative ages because, although early paleontologists understood biological succession, they did not know the absolute ages of the different organisms. It was only in the early part of the 20th century, when isotopic dating methods were first applied, that it became possible to discover the absolute ages of the rocks containing fossils. In most cases, we cannot use isotopic techniques to directly date fossils or the sedimentary rocks they are found in, but we can constrain their ages by dating igneous rocks that cut across sedimentary rocks, or volcanic layers that lie within sedimentary layers.

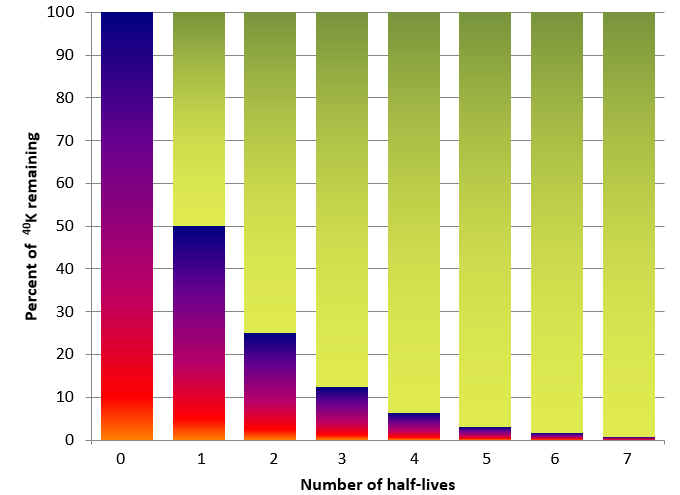

In nature, certain isotopes of elements are unstable, and will spontaneously decay to a different element as protons are lost or ejected from the nucleus of the atom. The unstable isotope that undergoes decay is often referred to as the parent isotope, and the product of its decay is referred to daughter product. Isotopic dating of rocks, or the minerals in them, is based on the fact that we know the decay rates of certain unstable isotopes of elements and that these rates have been constant over geological time. It is also based on the premise that when the atoms of an element decay within a mineral or a rock, they stay there and don’t escape to the surrounding rock, water, or air. One of the isotope pairs widely used in geology is the decay of 40K to 40Ar (potassium-40 to argon-40). 40K is a radioactive isotope of potassium that is present in very small amounts in all minerals that have potassium in them. It has a half-life of 1.3 billion years, meaning that over a period of 1.3 Ga one-half of the parent 40K atoms in a mineral or rock will decay to 40Ar daughter product, and over the next 1.3 Ga one-half of the remaining atoms will decay, and so on (Figure 4.5.1).

In order to use the K-Ar dating technique, we need to have an igneous or metamorphic rock that includes a potassium-bearing mineral. One good example is granite, which normally has some potassium feldspar (Figure 4.5.2). Feldspar does not have any argon in it when it forms, therefore any 40Ar we detect in the feldspar crystal had to have come from decay 40K. Over time, the 40K in the feldspar decays to 40Ar. Argon is a gas and the atoms of 40Ar remain trapped within the crystal, unless the rock is subjected to high temperatures after it forms. The sample must be analyzed using a very sensitive mass-spectrometer, which can detect the differences between the masses of atoms, and can therefore distinguish between 40K and the much more abundant 39K. Biotite and hornblende are also commonly used for K-Ar dating.

An important assumption that we have to be able to make when using isotopic dating is that when the rock formed none of the daughter isotope was present (e.g., 40Ar in the case of the K-Ar method). A clastic sedimentary rock is made up of older rock and mineral fragments, and when the rock forms it is almost certain that all of the fragments already have daughter isotopes in them. Furthermore, in almost all cases, the fragments have come from a range of source rocks that all formed at different times. If we dated a number of individual grains in the sedimentary rock, we would likely get a range of different dates, all older than the age of the rock. That could be useful information that might tell us about the source areas where sediments that make up the rock originally came from, but it would not provide an accurate date for the rock in question.

It might be possible to directly date some chemical sedimentary rocks isotopically, but there are no useful isotopes that can be used on old chemical sedimentary rocks. Radiocarbon dating can be used on sediments or sedimentary rocks that contain carbon, but it cannot be used on materials older than about 60 ka.

K-Ar is just one of many isotope-pairs that are useful for dating geological materials. Some of the other important pairs are listed in Table 4.2, along with the age ranges that they apply to and some comments on their applications. When radiometric techniques are applied to metamorphic rocks, the results normally tell us the date of metamorphism, not the date when the parent rock formed.

| [Skip Table] | |||

| Isotope System | Half-Life | Useful Range | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Potassium-argon | 1.3 Ga | 10 Ka to 4.57 Ga | Widely applicable because most rocks have some potassium |

| Uranium-lead | 4.5 Ga | 1 Ma to 4.57 Ga | The rock must have uranium-bearing minerals, but most have enough. |

| Rubidium-strontium | 47 Ga | 10 Ma to 4.57 Ga | Less precision than other methods at old dates |

| Carbon-nitrogen (a.k.a. radiocarbon dating) | 5,730 years | 100 to 60,000 years | Sample must contain wood, bone, or carbonate minerals; can be applied to young sediments |

Exercise 4.3 Isotopic dating

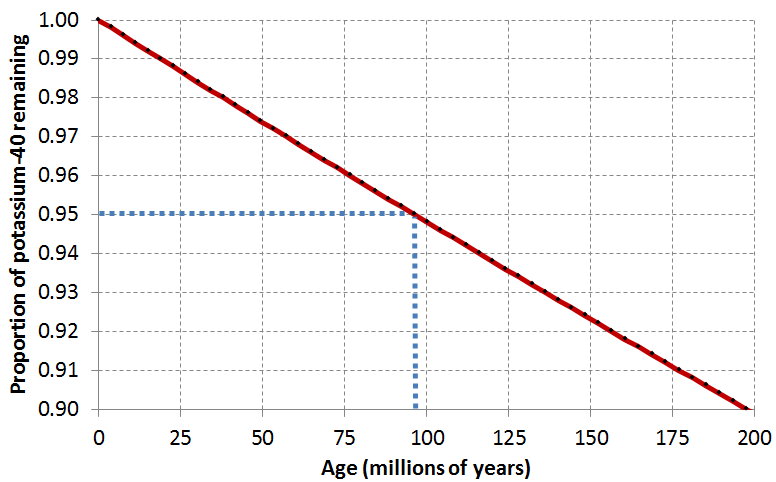

Assume that a feldspar crystal from the granite shown in Figure 4.5.4 was analyzed for 40K and 40Ar. The proportion of 40K remaining is 0.91. Using the decay curve shown on the graph below, estimate the age of the rock.

An example is provided (in blue) for a 40K proportion of 0.95, which is equivalent to an age of approximately 96 Ma. This is determined by drawing a horizontal line from 0.95 to the decay curve line, and then a vertical line from there to the time axis. See Appendix 3 for Exercise 4.3 answers.

The isotopic method that most people have heard of is likely radiocarbon dating. Radiocarbon dating (using 14C) can be applied to many geological materials, including sediments and sedimentary rocks. Note that the half-life for 14C is only 5,730 years! Because of this short half-life, a the majority of parent 14C will decay to daughter 14N in a relatively short amount of (geologic) time, so the materials in question must be younger than 60 ka. Fragments of wood or charcoal incorporated into young sediments are good candidates for carbon dating, and this technique has been used widely in studies involving late Pleistocene glaciers and glacial sediments, or young sediments cut by earthquake generating faults. An example is shown in Figure 4.5.5; radiocarbon dates charcoal within layers of glacial sediment that have been cut by the Teton fault are used to estimate the frequency with which surface rupturing earthquakes occur in this part of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. From these data, researchers have determined 3 major earthquakes have occurred on the Teton Fault within the last 10,000 years. One at ~10 ka, another at 8 ka, and the most recent at 5.9 ka. That is geologically YOUNG!

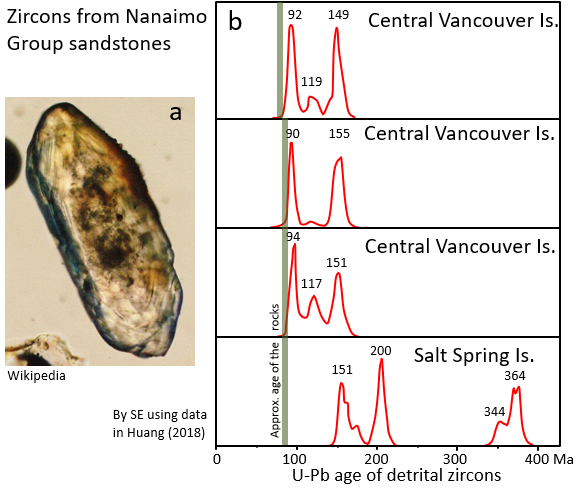

Another fascinating application is the use of U-Pb dating to study sedimentary rocks, not necessarily to find out the age of the rock, but to discover something about its history and origins. You think of it almost as a finger print or the DNA of a sedimentary rock. All clastic sedimentary rocks contain some tiny clasts of the silicate mineral zircon (ZrSiO4), derived from the weathering of the sediment parent rocks that were derived from different areas, just like you contain the DNA of your parents. Zircon is a very tough mineral, so it survives for a long time in the environment, in fact the oldest mineral geologists have ever dated on Earth is a zircon grain from Australia that is 4.3 billion years old. Zircon always has some uranium in it (but no lead) so it is a good candidate for U-Pb dating, and it isn’t too difficult to separate the grains of zircon from the other grains in a sandstone. The procedure is to isolate a few hundred tiny zircons from a rock sample, and then carry out U-Pb dating on each one of them, usually with a laser. An example of the types of results obtained are shown on Figure 4.5.6. All of the samples are from Nanaimo Group rocks on Vancouver Island and nearby Salt Spring Island, Canada.

The three samples from Vancouver Island have zircons aged around 90 Ma, 118 Ma and 150 Ma. The Salt Spring Island sample has some zircons aged around 150 Ma, but most are much older, at 200 Ma and 340 to 360 Ma. It is interpreted that the younger zircons (90 to 150 Ma) are mostly derived from granitic rocks in the Coast Range, while the older ones (>200 Ma) are from older rocks on Vancouver Island (Huang, 2018).

Image Descriptions

Media Attributions

- Physical Geology-2nd Edition, by Steven Earle is licensed under CC BY 4.0, adapted from the original by Ryan B. Anderson.

- Digging Into the Past on the Teton Fault, by USGS Earthquake Hazards is licensed under Public Domain, adapted from the original by Ryan B. Anderson

- Teton Fault, by the National Park Service is licensed under Public Domain, adapted from the original by Ryan B. Anderson.

- Figures 4.5.1, 4.5.2, 4.5.3, 4.5.4: © Steven Earle. CC BY.

- Figure 4.5.5: © USGS. Public Domain.

- Figure 4.5.6 (left): “Zircon microscope” © Chd. CC BY-SA.

- Figure 4.5.6b: © Steven Earle. CC BY. From data in Huang, C, 2018, Refining the chronostratigraphy of the lower Nanaimo Group, Vancouver Island, Canada, using Detrital Zircon Geochronology, MSc thesis, Department of Earth Science, Simon Fraser University, 74 p.

an form of an element that differs from other forms because it has a different number of neutrons (e.g., 16O has 8 protons and 8 neutrons while 18O has 8 protons and 10 neutrons)