Chapter 2 An introduction to Yellowstone and the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem

2.3 Introduction to the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem

What is the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem

What defines an ecosystem? It is a system that includes all living organisms (biotic factors) in a geographic area, as well as the physical environment (abiotic factors), functioning together and interacting as a unit.

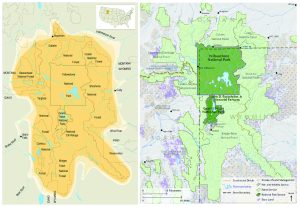

At 3,437.5 square miles (8,903 km2),Yellowstone National Park forms the core of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE)—one of the largest nearly intact temperate-zone ecosystems on Earth (Figure 2.3.2). Greater Yellowstone’s diversity of natural wealth includes the hydrothermal features, wildlife, vegetation, lakes, and geologic wonders like the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone River.

Yellowstone National Park was established in 1872 primarily to protect geothermal areas that contain about half the world’s active geysers. At that time, the natural state of the park was largely taken for granted. As development throughout the West increased, the 2.2 million acres (8,903 km2) of habitat that now compose Yellowstone National Park became an important sanctuary for the largest concentration of wildlife in the lower 48 states. Today, the GYE is home to one of the largest elk herds in North America, the largest wild and free-roaming herd of bison in the U.S., one of the free grizzly populations in the contiguous U.S., and at the forefront of the reintroduction of wolves to the Northern Rockies of the U.S. The abundance and distribution of these animal species depend on their interactions with each other and on the quality of their habitats, which in turn is the result of thousands of years of volcanic activity, forest fires, changes in climate, and more recent natural and human influences. Most of the park is above 7,500 feet (2,286 m) in elevation and underlain by volcanic bedrock. The terrain is covered with snow for much of the year and supports forests dominated by lodgepole pine and interspersed with alpine meadows. Sagebrush steppe and grasslands on the park’s lower-elevation ranges provide essential winter forage for elk, bison, and bighorn sheep.

The exact boundaries of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem are difficult to define given that the size, boundaries, and description of any ecosystem may vary, and there are no fences that can keep plants, animals, climatic effects, and Earth processes in or out of any given area (Figure 2.3.2 left). Though Yellowstone National Park comprises the core of the GYE, the GYE also includes state lands that encompass parts of Montana, Wyoming, and Idaho, two national parks (Yellowstone and Teton National Park), portions of five national forests, three national wildlife refuges, Bureau of Land Management holdings, private lands, and tribal lands (Figure 2.3.2 right). As such, land within the ecosystem is managed by many different entities: state governments, different agencies within the federal government, tribal governments, and private individuals and organizations.

Influence of Geology on the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem

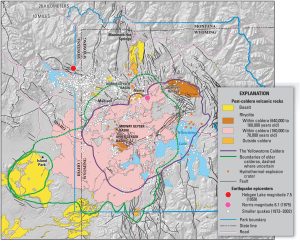

Geological characteristics form the foundation of an ecosystem. In Yellowstone, the interplay between volcanic, hydrothermal and glacial processes, and the distribution of flora and fauna, are intricate. The topography of the land from southern Idaho northeast to Yellowstone probably results from millions of years of hot-spot influence. Some scientists believe the Yellowstone Plateau itself is a result of uplift due to hot-spot volcanism. Today’s landforms even influence the weather, channeling westerly storm systems onto the plateau where they drop large amounts of snow.

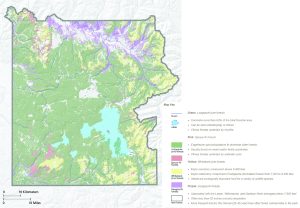

The volcanic rhyolites and tuffs of the Yellowstone Caldera are rich in quartz and potassium feldspar, which form nutrient-poor soils. Thus, areas of the park underlain by rhyolites and tuffs generally are characterized by extensive stands of lodgepole pine, which are drought-tolerant and have shallow roots that take advantage of the nutrients in the soil.

In contrast, andesitic volcanic rocks that underlie the Absaroka Mountains are rich in calcium, magnesium, and iron. These minerals weather into soils that can store more water and provide better nutrients than rhyolitic soils. These soils support more vegetation, which adds organic matter and enriches the soil. You can see the result when you drive over Dunraven Pass or through other areas of the park with Absaroka rocks. They have a more diverse flora, including mixed forests interspersed with meadows. Lake sediments deposited during glacial periods, such as those underlying Hayden Valley, form clay soils that allow meadow communities to outcompete trees for water. The patches of lodgepole pines in Hayden Valley grow in areas of rhyolite rock outcrops.

Because of the influence rock types, sediments, and topography have on plant distribution, some scientists theorize that geology also influences wildlife distribution and movement. Whitebark pine nuts are an important food source for grizzly bears during autumn. The bears migrate to whitebark pine areas such as the andesitic volcanic terrain of Mount Washburn. Grazing animals such as elk and bison favor the park’s grasslands, which grow best in soils formed by sediments in valleys such as Hayden and Lamar. The many hydrothermal areas of the park, where grasses and other food remain uncovered by snow, provide sustenance for animals during winter.

Water in Yellowstone

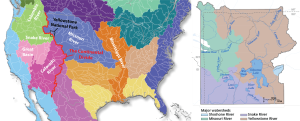

Not only is Yellowstone National Park the heart of the GYE, it also straddles the Continental Divide of North America. The water flowing through Yellowstone and the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE) is a vital national resource. The headwaters of seven great rivers located here flow from the Continental Divide across the nation to the Pacific Ocean, and the gulfs of California and Mexico. Rain and snow in the mountains and plateaus of the Northern Rockies flow through stream and river networks to provide essential moisture to much of the American West. Together, Yellowstone’s streams and rivers support an abundance of fish and wildlife, provide numerous recreational opportunities, and offer a lifeline for downstream agricultural users and municipalities.

Water also drives the complex geothermal activity in the region and fuels the largest collection of geysers on Earth. Precipitation and groundwater seep down into geothermal “plumbing” over days, and millennia, to be superheated by the Yellowstone Volcano and rise to the surface in the form of hot springs, geysers, mudpots, and fumaroles.

Yellowstone contains some of the most significant, near-pristine aquatic ecosystems found in the United States. More than 600 lakes and ponds comprise approximately 107,000 surface acres in Yellowstone—94 percent of which can be attributed to Yellowstone, Lewis, Shoshone, and Heart lakes. Some 1,000 rivers and streams make up approximately 2,500 miles of running water. Thousands of small wetlands—habitats that are intermittently wet and dry—make up a small (approximately 3%), fraction of the Yellowstone landscape.

Media Attributions

- Yellowstone Resources and Issues Handbook, by the National Park Service is Public Domain. Minor modifications were made to the text by Ryan B. Anderson.

- Figure 2.3.1 © Ryan B. Anderson. CC BY.

- Figure 2.3.2 left, Map of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, National Park Service, Public Domain.

- Figure 2.3.2 right, The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, Yellowstone Resources and Issues Handbook, National Park Service, Public Domain.

- Figure 2.3.3 Simplified map of Yellowstone caldera, United States Geological Survey, Public Domain.

- Figure 2.3.4 Vegetation Communities, NPS/Yellowstone Spatial Analysis Center, Public Domain.

- Figure 2.3.5 left, Base map is the Watershed Map of North America, United States Geological Survey, Public Domain, with modifications added by Ryan B. Anderson.

- Figure 2.3.5 right, Major watersheds in Yellowstone National Park, National Park Service/Yellowstone Spatial Analysis Center, Public Domain.