Chapter 2 An introduction to Yellowstone and the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem

2.2 Is Yellowstone a “Supervolcano”?

Is Yellowstone a “Supervolcano”?

Yellowstone national park overlies one of Earth’s largest and potentially most destructive volcanoes, which is no secret given the copious amounts of thermal features like hot springs and geysers that can be found all over the park. Inevitably, you have probably heard that Yellowstone is a “supervolcano” overdue to erupt, and end life as we know it on Earth! Search the term “Yellowstone supervolcano eruption” on youtube and you will be treated to an endless list of incorrect, misinformed, and down right fictional lies about the threat of the so called “supervolcano”. However, if you asked an expert in the field of volcanology that actually studies Yellowstone if there is a danger of a “supervolcano” eruption, what would they say? First, they would say please stop calling it a “supervolcano”. The term “supervolcano” is a colloquial term with no scientific definition, the preferred term is the Yellowstone caldera system or Yellowstone caldera complex. Second, they would say that it is a misconception that the Yellowstone caldera complex is overdue for a massive, Armageddon like eruption. The Yellowstone caldera complex is under constant surveillance by the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory, which is continuously monitoring earthquake activity, ground surface deformation, changes to water temperature or chemistry, and other variables that can tell us about movement of magma below the surface. The current assessment by the experts is that a massive volcanic eruption from the Yellowstone caldera complex is not likely in our lifetime.

Some confusion may come from the fact that the term super eruption is an actual term used by volcanologists to describe the magnitude of an eruptive event. The Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI) is a scale used to describe the size of explosive volcanic events (Figure 2.2.1). Similar to the earthquake magnitude scale, the scale is logarithmic, meaning each interval on the scale represents a tenfold increase in the volume of material ejected. For example, an event with a rank of 4 is ten times larger than an event with a rank of 3. Volume of products, eruption cloud height, and qualitative observations (using terms ranging from “gentle” to “mega-colossal”) are used to determine the explosivity value. Any eruption greater than a magnitude 8 on the VEI scale would be considered a super eruption. To put into perspective just how large a super eruption is, consider the June 12th, 1980 Mount St Helens eruption, which was the most destructive volcanic eruption in U.S. history (keeping in mind U.S. history only goes back a few hundred years). According to the VEI scale, the Mount St Helens eruptions was ~1000 times SMALLER than a super eruption.

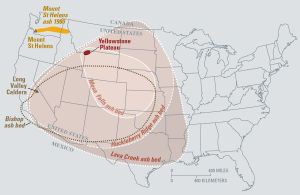

Where does the Yellowstone caldera complex get it’s reputation as a “supervolcano”? The reality is that the Yellowstone caldera system has a ~17 million year history of producing super eruptions that have ejected material as far as Mississippi, and is capable of producing super eruptions today. Consider the three most recent super eruptions from the Yellowstone caldera system that produced thick ash layers (Figure 2.2.2): The Huckleberry Ridge Tuff (2.1 million years ago), the Mesa Falls Tuff (1.3 million years ago), and the Lava Creek Tuff (630,000 years ago). The event that produced the Huckleberry Ridge Tuff is rated as an 8.7 on the VEI, and the event produced the Mesa Falls Tuff was rated as an 8.3 on the VEI scale! That being said, not every volcanic eruption from the Yellowstone caldera is a super eruption. The most recent volcanic activity was the Pitchstone Plateau flow, which was a small volume of lava that erupted only 70,000 years ago.

So where does that leave us? Should you be worried about a cataclysmic super eruption from the Yellowstone caldera system? Probably not. The geoscientists that monitor the caldera system are able to image the interior of Earth and the magma chamber below Yellowstone. The two key ingredients needed for a super eruption is enough volume of magma in the magma chamber, and enough build up of pressure to overcome the confining pressure of the overlying crust above the magma chamber. Fortunately, the data indicates that the magma reservoir contains only ~5-15% molten material, and that you would typically need at least 50% melt of the magma to begin moving toward the surface. The most likely hazard to affect someone visiting or living near the park would be a hydrothermal explosion from a geyser, or an earthquake.

As you read forward through this book, a clearer picture will emerge as to why volcanic eruptions occur, the different compositions of magmas we observe on Earth, why earthquakes occur in our region and adjacent to Yellowstone, and why Yellowstone can produce such explosive eruptions.

Media attibutions

- Don’t call it a supervolcano

- Five Things Most People Get Wrong About the Yellowstone Volcano

- Questions About Monitoring Yellowstone

- Figure 2.2.1 USGS, Public Domain

- Figure 2.2.2 USGS, Public Domain