Chapter 12 Earthquakes

12.8 The 1959 Hebgen Lake Earthquake

As noted in section 12.7, most earthquakes in the Yellowstone region are in the M0–2 range, there are always a few that are M3 or higher and that are felt by people in the area. The largest quake of the past several years was a M4.8 that occurred near Norris Geyser Basin in March 2014 and that was felt widely across the area. Between 2020 and 2010, there were 54 felt events in the Yellowstone region giving an average of ~5 felt earthquakes every year. However, of the 54 felt events, 38 were part of either the 2010 Madison Plateau swarm or the 2017-2018 Maple Creek swarm. So while there is always a chance that visitors to Yellowstone will feel an earthquake, the chances increase if there is a significant swarm occurring!

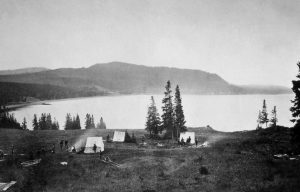

In fact, some of the first “tourists” to Yellowstone felt earthquakes. In 1871, Ferdinand V. Hayden led a federally funded expedition to the Yellowstone region to explore the many wonders in the area. While camping on the north shore of Yellowstone Lake (near current Steamboat Point), they recorded the following passage:

“This morning [August 20] about 1 o’clock we had quite an earthquake. The first schock [sic] lasted about 20 seconds and was followed by five or six shorter ones. Duncan, who was on guard, says that the trees were shaken and that the horses that were lying on the ground sprang to their feet … We had three shocks during the morning.”

Because of the earthquakes that they felt in this area, they named this camp “Earthquake Camp” (Figure 12.8.1). These earthquakes were probably part of a swarm.

Anytime you visit Yellowstone, it is virtually guaranteed that there will be earthquakes occurring while you are there. The odds are that you won’t feel any of these quakes, but there’s always a chance that a felt event may occur, and an outside chance that the event could be strong, like those that have struck the Yellowstone area in the past. Yellowstone is earthquake country, and one of the largest and deadliest earthquakes in the intermountain west occurred here in 1959: The Hebgen Lake Earth Quake.

The 1959 M7.3 Hebgen Lake Earthquake

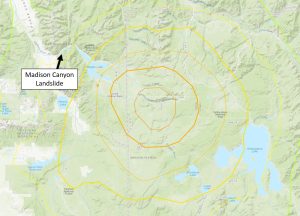

The Hebgen Lake earthquake occurred on August 17th, 1959 at 11:37 PM (MST). The magnitude 7.3 earthquake had an epicenter located just outside the western boundary of Yellowstone National Park, ~6.5 miles WNW of West Yellowstone, Montana (Figure 12.8.2).

The earthquake caused 28 fatalities, with most of those as a result of a large landslide that was triggered in the Madison Canyon. That landslide carried ~50 million cubic yards of rock, mud, and debris down the south side of the canyon and half way up the north side, partially burying the Rock Creek campground on the valley floor. The landslide also dammed the Madison River, causing water to back up behind it creating EarthquakeLake.

The combination of the landslide, fault scarps, and damaged highways trapped many tourists in the canyon that night. In addition, the sudden northward tilting of the basin caused Hebgen Lake to slosh back and forth. This is referred to a seiche wave. The waves were so large that they breached the Hebgen Lake dam a few times, leading panicked tourists to think the dam had failed. Luckily, the dam did not fail and the waves eventually died off.

The earthquake caused up to ~18-20 feet of offset on the surface (fault scarps) that can still be seen today on both the Hebgen Lake and Red Canyon faults and, to a lesser extent, the Madison fault (Figure 12.8.4). Within nearby Yellowstone National Park, many rock slides blocked the roadways, and there was damage to the world famous Old Faithful Inn, where a large rock chimney collapsed.

But maybe even more spectacular were the effects of the earthquake on the hydrothermal features in Yellowstone National Park. By the day after the earthquake, at least 289 springs in the geyser basins of the Firehole River had erupted as geysers; of these, 160 were springs with no previous record of eruption. At least 590 springs had become turbid. During the first few days after the earthquake, most springs began to clear, but several years passed before clearing was generally complete. In addition, new hot ground soon developed in some places and this became more apparent by the following spring with the formation of new fractures in sinter and linear zones of dead or dying trees. Some new fractures developed locally into fumaroles, and a few of these evolved into hot springs or geysers.

Two of the most spectacular changes were the formation of Seismic Geyser and the changes to Sapphire Pool. Seismic geyser (located in the Upper Geyser Basin) started out as a newly formed fracture after the Hebgen Lake earthquake. The fracture slowly evolved into a fumarole, and in about 2.5 years it evolved into a small geyser. A few years later, it had changed into a very vigorous geyser that erupted to heights up to 50 feet and excavated a vent with a maximum diameter of ~40 feet and more than 20 feet deep. In 1971, major eruptions ceased at Seismic geyser as activity shifted to a new, small, satellite crater that formed nearby.

Prior to the Hebgen Lake earthquake, Sapphire Pool (located in Biscuit Basin) erupted about every 17 to 20 minutes to a height of 3 to 6 feet. Following the quake, and until September 5, it surged 6 to 8 feet high constantly. On September 5, its steady boiling and surging became periodic, and the spring changed into a major geyser. Its eruptions were quite regular, occurring about every 2 hours, and were massive and spectacular; some of the bursts were 150 feet high and 200 feet across! From September 14 to 29 it reverted to a steadily surging cauldron. On September 29 it again became a major geyser, and this activity persisted until 1968. Sapphire pool today is still a crystal-clear, blue-water pool, and it still violently boils and surges on occasion.

For the first few days after the earthquake, Old Faithful was observed to be more erratic than usual, with successive longer and shorter intervals between eruptions, but that had been observed prior to the earthquake as well. The average eruption interval the summer prior to the earthquake was 61.8 minutes—the shortest seasonal average on record. By September 1 it had increased to 62.1 minutes. Two hundred and fifty-five eruption intervals timed during the last 10 days of December showed an average interval of 67.4 minutes. Old Faithful’s eruption interval has continued to increase since that time and is now averaging ~93 minutes. Was this a direct result of the Hebgen Lake earthquake?

The Hebgen Lake earthquake continues to be the largest earthquake to occur in the U.S. Intermountain West in historic times. Earthquakes happen nearly every day in the region, and occasionally the area produces strong earthquakes that are capable of affecting large areas and causing damage. We should expect similar effects if another earthquake of this size would to happen today, except there are many more people visiting the area today than there were in the summer of 1959. The more we are prepared for earthquakes, the better we will be after one happens.

Media attributions

- Earthquakes in and around Yellowstone: How often do they occur? remixed by Ryan B. Anderson

- 60 years since the 1959 M7.3 Hebgen Lake earthquake: its history and effects on the Yellowstone region, remixed by Ryan B. Anderson

- Figure 12.8.1, National Park Service, Public Domain

- Figure 12.8.2, USGS Interactive Map of the M 7.3 – The 1959 Hebgen Lake, Montana Earthquake, Public Domain, Modified by Ryan B. Anderson

- Figure 12.8.3, © Ryan B. Anderson. CC BY.

- Figure 12.8.4, J.R. Stacy, USGS, Public Domain

- Figure 12.8.5, USGS, Public Domain