Chapter 5 Minerals

The Earth is made up of varying proportions of the 90 naturally occurring elements—hydrogen, carbon, oxygen, magnesium, silicon, iron, and so on. In most geological materials, these combine in various ways to make minerals.

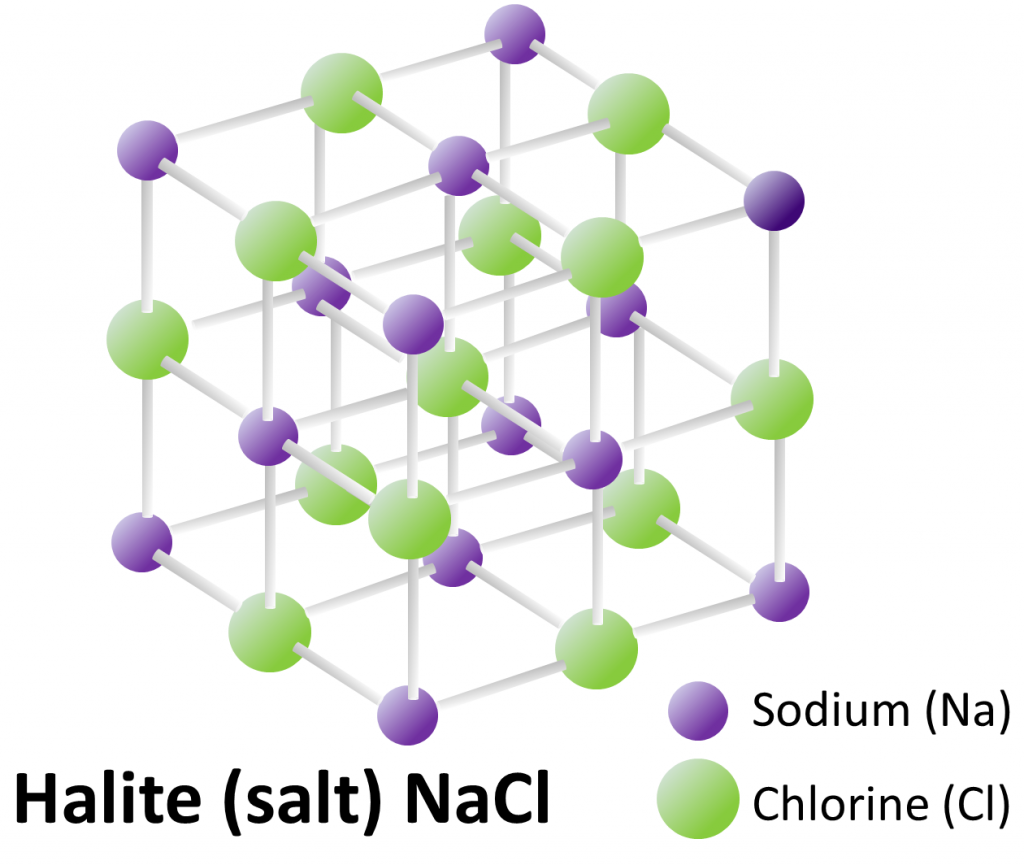

As noted in the intro to this chapter, a mineral is a naturally occurring combination of specific elements that are arranged in a particular repeating three-dimensional structure or lattice. The mineral halite is shown as an example in Figure 5.1.1.

In this case, atoms of sodium (Na: purple) alternate with atoms of chlorine (Cl: green) in all three dimensions, and the angles between the bonds are all 90°. Even in a tiny crystal, like the ones in your salt shaker, the lattices extend in all three directions for thousands of repetitions. Halite always has this composition and this structure.

| Note: Element symbols (e.g., Na and Cl) are used extensively in this book. In Appendix 1, you will find a list of the symbols and names of the elements common in minerals and a copy of the periodic table. Please use those resources if you are not familiar with the element symbols. |

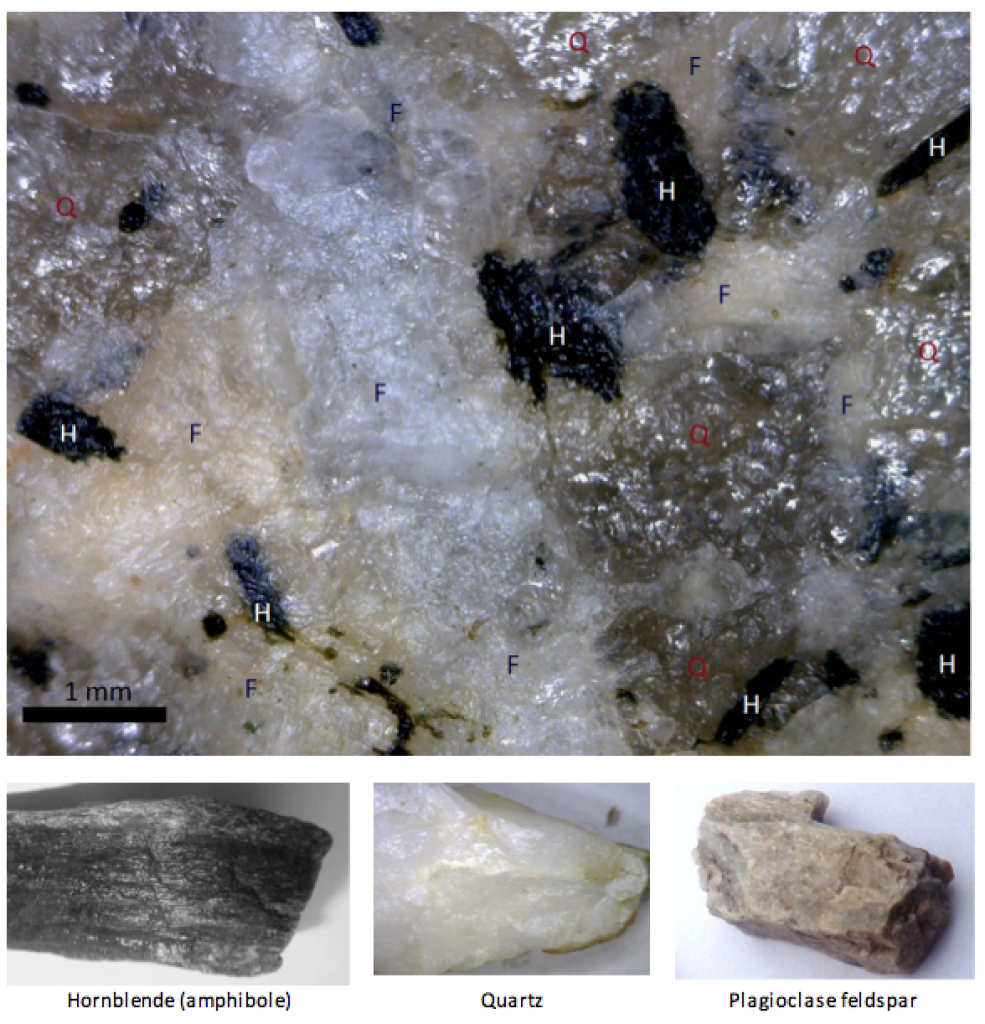

There are over 4000 thousand known minerals that have been characterized and named by geoscientists, although only a few dozen are mentioned in this book. In nature, minerals are found in rocks, and the vast majority of rocks are composed of at least a few different minerals. The nine most common rock forming minerals on Earth, known colloquially as the “notable nine” are: quartz, olivine, muscovite, biotite, pyroxene, hornblende, potassium feldspar, plagioclase feldspar, and calcite. A close-up view of granite, a common rock, is shown in Figure 5.1.2. Although a hand-sized piece of granite may have thousands of individual mineral crystals in it, there are typically only a few different minerals, as shown here.

Rocks can form in a variety of ways, which are discussed in more detail in subsequent chapters. Igneous rocks form from magma (molten rock) that has either cooled slowly underground (e.g., to produce granite) or cooled quickly at the surface after a volcanic eruption (e.g., basalt). Sedimentary rocks, such as sandstone, form when the weathered products of other rocks accumulate at the surface and are then buried by other sediments. Metamorphic rocks form when either igneous or sedimentary rocks are heated and squeezed to the point where some of their minerals are unstable and new minerals form to create a different type of rock. An example is schist.

A critical point to remember is the difference between a mineral and a rock. A mineral is a pure substance with a specific composition and structure, while a rock is typically a mixture of several different minerals (although a few types of rock may include only one type of mineral). Examples of minerals are feldspar, quartz, mica, halite, calcite, and amphibole. Examples of rocks are granite, basalt, sandstone, limestone, and schist.

Key Takeaway: Know the difference between minerals and rocks!

If you are currently taking a geology course, you’ll likely be asked more than once to name a mineral or a rock that has specific characteristics or composition, or was formed in a specific environment. Please make sure that if you’re asked for a rock name that you don’t respond with a mineral name, and vice versa. Confusing minerals and rocks is one of the most common mistakes that geology students make.Exercise 1.1 Find a piece of granite

Media Attributions

- Physical Geology-2nd Edition, by Steven Earle is licensed under CC BY 4.0, Modified from the original by Ryan B. Anderson.

- Figure 5.1.1, 5.1.2: © Steven Earle. CC BY.

The regular and repeating three-dimensional structure of a mineral.

NaCl, a halide mineral also known as table salt.

A felsic intrusive igneous rock.

Molten rock typically dominated by silica.

A volcanic rock of mafic composition.

A rock that is primarily comprised of sand-sized particles.

A metamorphic rock with visible aligned mica crystals.