Chapter 1 Introduction to Geoscience

1.1 The Process of Science

Matthew R. Fisher

Like other natural sciences, geology or geoscience is a science that gathers knowledge about the natural world. The methods of science include careful observation, record keeping, logical and mathematical reasoning, experimentation, and submitting conclusions to the scrutiny of others. Science also requires considerable imagination and creativity; a well-designed experiment is commonly described as elegant or beautiful. Science has considerable practical implications and some science is dedicated to practical applications, such as the prevention of disease (figure 1.2). Other science proceeds largely motivated by curiosity. Whatever its goal, there is no doubt that science has transformed human existence and will continue to do so.

The Nature of Science

Geology is a science, but what exactly is science? What does the study of geology share with other scientific disciplines? Science (from the Latin scientia, meaning “knowledge”) can be defined as a process of gaining knowledge about the natural world.

Science is a very specific way of learning about the world. The history of the past 500 years demonstrates that science is a very powerful way of gaining knowledge about the world; it is largely responsible for the technological revolutions that have taken place during this time. There are areas of knowledge, however, that the methods of science cannot be applied to. These include such things as morality, aesthetics, or spirituality. Science cannot investigate these areas because they are outside the realm of material phenomena, the phenomena of matter and energy, and cannot be observed and measured.

The scientific method is a method of research with defined steps that include experiments and careful observation. The steps of the scientific method will be examined in detail later, but one of the most important aspects of this method is the testing of hypotheses. A hypothesis is an proposed explanatory statement, for a given natural phenomenon, that can be tested. Hypotheses, or tentative explanations, are different than a scientific theory. A scientific theory is a widely-accepted, thoroughly tested and confirmed explanation for a set of observations or phenomena. Scientific theory is the foundation of scientific knowledge. In addition, in many scientific disciplines there are scientific laws, often expressed in mathematical formulas, which describe how elements of nature will behave under certain specific conditions, but they do not offer explanations for why they occur.

Natural Sciences

What would you expect to see in a museum of natural sciences? Frogs? Plants? Dinosaur skeletons? Exhibits about how the brain functions? A planetarium? Gems and minerals? Or maybe all of the above? Science includes such diverse fields as astronomy, computer sciences, psychology, biology, and mathematics. However, those fields of science related to the physical world and its phenomena and processes are considered natural sciences and include the disciplines of physics, geology, biology, and chemistry.

Scientific Inquiry

One thing is common to all forms of science: an ultimate goal to know. Curiosity and inquiry are the driving forces for the development of science. Scientists seek to understand the world and the way it operates. Two methods of logical thinking are used: inductive reasoning and deductive reasoning.

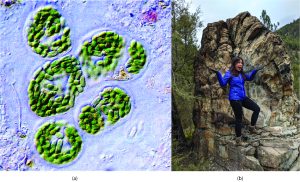

Inductive reasoning is a form of logical thinking that uses related observations to arrive at a general conclusion. This type of reasoning is common in descriptive science. A life scientist such as a biologist makes observations and records them. These data can be qualitative (descriptive) or quantitative (consisting of numbers), and the raw data can be supplemented with drawings, pictures, photos, or videos. For example, a geoscientist may observe a location with spherical rock formations (figure 1.3) and become curious as to how such a rock formation could form. A qualitative description of these rocks might be: “these rocks appear very round, and easily roll if pushed, they must be close to spherical in shape”. Whereas, a quantitative assessment of the same rocks could involve precise measurements of the rock to determine how close they are are to a perfect sphere. From many observations, the scientist can infer conclusions (inductions) based on evidence. For example, a geoscientist might look at other locations and environments on Earth where such spherical rocks can be found, and then infer conclusions based on evidence. Inductive reasoning involves formulating generalizations inferred from careful observation and the analysis of a large amount of data. A great example are brain studies. Many brains are observed while people are doing a task. The part of the brain that lights up, indicating activity, is then demonstrated to be the part controlling the response to that task.

Deductive reasoning or deduction is the type of logic used in hypothesis-based science. In deductive reasoning, the pattern of thinking moves in the opposite direction as compared to inductive reasoning. Deductive reasoning is a form of logical thinking that uses a general principle or law to forecast specific results. From those general principles, a scientist can extrapolate and predict the specific results that would be valid as long as the general principles are valid. For example, a prediction would be that if the climate is becoming warmer in a region, the distribution of plants and animals should change. Comparisons have been made between distributions in the past and the present, and the many changes that have been found are consistent with a warming climate. Finding the change in distribution is evidence that the climate change conclusion is a valid one.

Both types of logical thinking are related to the two main pathways of scientific study: descriptive science and hypothesis-based science. Descriptive (or discovery) science aims to observe, explore, and discover, while hypothesis-based science begins with a specific question or problem and a potential answer or solution that can be tested. The boundary between these two forms of study is often blurred, because most scientific endeavors combine both approaches. Observations lead to questions, questions lead to forming a hypothesis as a possible answer to those questions, and then the hypothesis is tested. Thus, descriptive science and hypothesis-based science are in continuous dialogue.

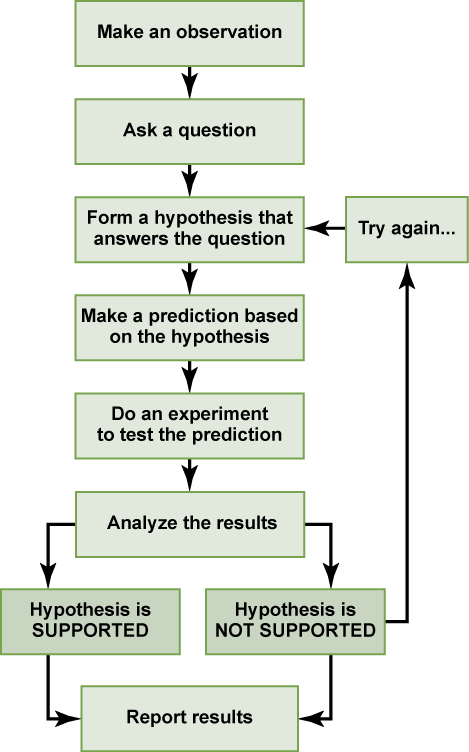

Hypothesis Testing

Geoscientists study the Earth by posing questions about it and seeking science-based responses. This approach is common to other sciences as well and is often referred to as the scientific method. The scientific method was used even in ancient times, but it was first documented by England’s Sir Francis Bacon (1561–1626) who set up inductive methods for scientific inquiry. The scientific method is not exclusively used by biologists but can be applied to almost anything as a logical problem-solving method.

The scientific process typically starts with an observation (often a problem to be solved) that leads to a question. Let’s think about a simple problem that starts with an observation and apply the scientific method to solve the problem. One Monday morning, a student arrives at class and quickly discovers that the classroom is too warm. That is an observation that also describes a problem: the classroom is too warm. The student then asks a question: “Why is the classroom so warm?”

Recall that a hypothesis is a suggested explanation that can be tested. To solve a problem, several hypotheses may be proposed. For example, one hypothesis might be, “The classroom is warm because no one turned on the air conditioning.” But there could be other responses to the question, and therefore other hypotheses may be proposed. A second hypothesis might be, “The classroom is warm because there is a power failure, and so the air conditioning doesn’t work.”

Once a hypothesis has been selected, a prediction may be made. A prediction is similar to a hypothesis but it typically has the format “If . . . then . . . .” For example, the prediction for the first hypothesis might be, “If the student turns on the air conditioning, then the classroom will no longer be too warm.”

A hypothesis must be testable ensure that it is valid. It should also be falsifiable, meaning that it can be disproven by experimental results. These two key points differentiate science from pseudoscience. For example, a hypothesis that depends on what a bear thinks is not testable, because it can never be known what a bear thinks. An example of an unfalsifiable hypothesis is “Botticelli’s Birth of Venus is beautiful.” There is no experiment that might show this statement to be false. To test a hypothesis, a researcher will conduct one or more experiments designed to eliminate one or more of the hypotheses. This is important. A hypothesis can be disproven, or eliminated, but it can never be proven. Science does not deal in proofs like mathematics. If an experiment fails to disprove a hypothesis, then we find support for that explanation, but this is not to say that down the road a better explanation will not be found, or a more carefully designed experiment will be found to falsify the hypothesis.

Each experiment will have one or more variables and one or more controls. Experimental variables are any part of the experiment that can vary or change during the experiment. Controlled variables are parts of the experiment that do not change. Lastly, experiments might have a control group: a group of test subjects that are as similar as possible to all other test subjects, with the exception that they don’t receive the experimental treatment (those that do receive it are known as the experimental group). For example, in a study testing a weight-loss drug, the control group would be test subjects that don’t receive the drug (but they might receive a placebo, such as sugar pill, instead). Look for these various things in the example that follows:

An experiment might be conducted to test the hypothesis that phosphate (a nutrient) promotes the growth of algae in freshwater ponds. A series of artificial ponds are filled with water and half of them are treated by adding phosphate each week, while the other half are treated by adding a non-nutritional mineral that is not used by algae. The experimental variable here is presence/absence of a nutrient (phosphate). One potential controlled variable would be the volume of water in each tank. The amount of water that algae have access to may influence the results, thus researchers want to control its influence on the results by making sure all test subjects get the same amount. The control group consists of the tanks that received a placebo (non-nutritional mineral) instead of the phosphate. If the ponds with phosphate show more algal growth, then we have found support for the hypothesis. If they do not, then we reject our hypothesis. Be aware that rejecting one hypothesis does not determine whether or not the other hypotheses can be accepted; it simply eliminates one hypothesis that is not valid (Figure 1.5). Using the scientific method, the hypotheses that are inconsistent with experimental data are rejected.

In the example below, the scientific method is used to solve an everyday problem. Which part in the example below is the hypothesis? Which is the prediction? Based on the results of the experiment, is the hypothesis supported? If it is not supported, propose some alternative hypotheses.

- My toaster doesn’t toast my bread.

- Why doesn’t my toaster work?

- There is something wrong with the electrical outlet.

- If something is wrong with the outlet, my coffeemaker also won’t work when plugged into it.

- I plug my coffeemaker into the outlet.

- My coffeemaker works.

In practice, the scientific method is not as rigid and structured as it might at first appear. Sometimes an experiment leads to conclusions that favor a change in approach; often, an experiment brings entirely new scientific questions to the puzzle. Many times, science does not operate in a linear fashion; instead, scientists continually draw inferences and make generalizations, finding patterns as their research proceeds. Scientific reasoning is more complex than the scientific method alone suggests.

Basic and Applied Science

Is it valuable to pursue science for the sake of simply gaining knowledge, or does scientific knowledge only have worth if we can apply it to solving a specific problem or bettering our lives? This question focuses on the differences between two types of science: basic science and applied science.

Basic science or “pure” science seeks to expand knowledge regardless of the short-term application of that knowledge. It is not focused on developing a product or a service of immediate public or commercial value. The immediate goal of basic science is knowledge for knowledge’s sake, though this does not mean that in the end it may not result in an application.

In contrast, applied science aims to use science to solve real-world problems, such as improving crop yield, find a cure for a particular disease, predict the location of natural resources, or save animals threatened by a natural disaster. In applied science, the problem is usually defined for the researcher.

Some individuals may perceive applied science as “useful” and basic science as “useless.” A question these people might pose to a scientist advocating knowledge acquisition would be, “What for?” A careful look at the history of science, however, reveals that basic knowledge has resulted in many remarkable applications of great value. Many scientists think that a basic understanding of science is necessary before an application is developed; therefore, applied science relies on the results generated through basic science. Other scientists think that it is time to move on from basic science and instead to find solutions to actual problems. Both approaches are valid. It is true that there are problems that demand immediate attention; however, few solutions would be found without the help of the knowledge generated through basic science.

One example of how basic and applied science can work together to solve practical problems occurred after the discovery of DNA structure led to an understanding of the molecular mechanisms governing DNA replication. Strands of DNA, unique in every human, are found in our cells, where they provide the instructions necessary for life. During DNA replication, new copies of DNA are made, shortly before a cell divides to form new cells. Understanding the mechanisms of DNA replication (through basic science) enabled scientists to develop laboratory techniques that are now used to identify genetic diseases, pinpoint individuals who were at a crime scene, and determine paternity (all examples of applied science). Without basic science, it is unlikely that applied science would exist.

Another example of the link between basic and applied research is the Human Genome Project, a study in which each human chromosome was analyzed and mapped to determine the precise sequence of the DNA code and the exact location of each gene. (The gene is the basic unit of heredity; an individual’s complete collection of genes is his or her genome.) Other organisms have also been studied as part of this project to gain a better understanding of human chromosomes. The Human Genome Project (Figure 1.6) relied on basic research carried out with non-human organisms and, later, with the human genome. An important end goal eventually became using the data for applied research seeking cures for genetic diseases.

Scientific Work is Transparent & Open to Critique

Whether scientific research is basic science or applied science, scientists must share their findings for other researchers to expand and build upon their discoveries. For this reason, an important aspect of a scientist’s work is disseminating results and communicating with peers. Scientists can share results by presenting them at a scientific meeting or conference, but this approach can reach only the limited few who are present. Instead, most scientists present their results in peer-reviewed articles that are published in scientific journals. Peer-reviewed articles are scientific papers that are reviewed, usually anonymously by a scientist’s colleagues, or peers. These colleagues are qualified individuals, often experts in the same research area, who judge whether or not the scientist’s work is suitable for publication. The process of peer review helps to ensure that the research described in a scientific paper or grant proposal is original, significant, logical, ethical, and thorough. Scientists publish their work so other scientists can reproduce their experiments under similar or different conditions to expand on the findings. The experimental results must be consistent with the findings of other scientists.

As you review scientific information, whether in an academic setting or as part of your day-to-day life, it is important to think about the credibility of that information. You might ask yourself: has this scientific information been through the rigorous process of peer review? Are the conclusions based on available data and accepted by the larger scientific community? Scientists are inherently skeptical, especially if conclusions are not supported by evidence (and you should be too).

Suggested Supplementary Reading:

Attribution

Environmental Biology by Matthew R. Fisher is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Minor modification from the original made by Ryan B. Anderson.

- Figures 1.1a, and 1.3: © Ryan B. Anderson: CC BY