Chapter 4 Measuring Geological Time

4.7 A Brief Geologic History of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem

Although the Yellowstone region is best known for it’s more recent history of spectacular super eruptions over the last ~2 million year, the rocks in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem record events in Earth history as far back as 3.5 BILLION years.

Building the Basement of Yellowstone

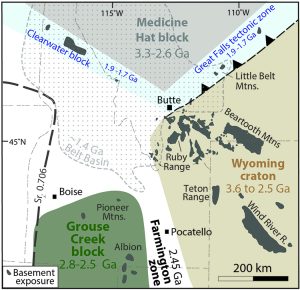

The core of the North American continent is an amalgamation of smaller continental fragments that were tectonically assembled together between about 3.5 billion years ago and 1.5 billion years ago. These “basement” rocks have a long tectonic history that includes being variably melted, squished, and buried deeply within the crust over their long lifespan, so they are mostly crystalline metamorphic and igneous rocks. You can think of them like the foundation your house is built on, hence why we call them basement rocks. Subsequent geologic events have deposited sedimentary and volcanic rocks on top of them, and the land mass of North America has been expanded laterally outward since 1.1 Ga on the east coast, and 0.6 Ga on the west coast (Figure 4.7.1). Figure 4.7.1 is a map of the basement terranes of North America, which are defined as different domains based on the characteristics of the basement rocks, as well as the age of the rocks. Though the map would make it seem as if the basement rocks are extensively exposed across North America, the reality is we only get tiny glimpses of the basement rock, mostly within mountain ranges that have been uplifted and eroded in the last few million years (Figure 4.7.2). In the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, the basement rocks are best exposed in the Teton Range, the Wind River Range, and the Bear Tooth Range (Figure 4.7.2). The basement rocks of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem belong to the Wyoming Craton. U-Pb ages indicated these rocks are up to ~3.8 billion years old, and were then intruded by younger magmas, metamorphosed, and deformed, particularly between ~2.9-2.5 billion years ago and ~1.8 billion years ago.

Paleozoic to Mesozoic Rise and Fall of Sea Level

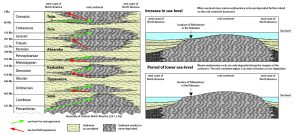

Most of the geology we can see in Yellowstone National Park and the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem occurred over the last ~600 million years. Today, the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem is a mountainous region that is far from the ocean, so it is hard to imagine that in the geologic past Wyoming and eastern Idaho were near coastal property, and were variably close to or below sea level throughout the Paleozoic and Mesozoic (~600-100 million years ago). Accordingly, the Paleozoic through Mesozoic rocks that are found in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem record repeated cycles of rising and falling sea-level. These rocks are a part of the cratonic sequences that are observed across all of North America known. A cratonic sequence is a series of stratigraphic layers that record a complete cycle of large scale sea-level rise and fall through geologic time. During periods of lower sea-level, the coast line moves away from the central part of the continent. Anything above sea-level is subject to erosional forces, so it is a region where erosion primarily takes place, so that very little sediment can accumulate to become rock layers. Whereas when level rises, the coastline moves inland and inundates the regions that were previously above sea-level. Along with the inward shift of the coastline, marine (or ocean) sedimentary rocks are deposited, which eventually solidify into layers of rock that preserve the record of sea-level rise. Six major sequences of rise and fall of sea-level are observed and recognized in North America: the Sauk, Tippecanoe, Kaskaskia, Absaroka, Zuni, and Tejas. Five of the six cycles occurred in the Yellowstone region with little geologic disruption. Such that from ~600-100 Ma (500 million years)….

Late Mesozoic Mountain Building

Near the close of the Mesozoic Era the earth was subjected to a series of intense crustal disturbances that geologists call the Sevier and Laramide orogenies (orogeny means mountain-building). Major upheaval began in southeastern Idaho by ~120 Ma, and reached the Yellowstone region by ~75 Ma. A significant effect of this event was the uplift and contortion of many of the mountain ranges within what we today call the Rocky Mountains. At the onset of the crustal disturbance, the gently rolling landscape of the Yellowstone region began to warp and flex into large upfolds (anticlines) and downfolds (synclines). Gradually the mountain-building pressures increased, finally reaching such magnitude that the limbs of the folds could bend and stretch no further; thereupon, the rock layers broke and were shoved over one another along extensive reverse faults. The severely crumpled rocks within the Park area can now be seen only along the north edge and in the south-central part along the Snake River. In both places, the folds and faults are especially well displayed by the layered Paleozoic and Mesozoic sedimentary formation

Cenozoic Basin and Range Extension

Volcanic Activity

Media Attributions

- Keefer, W.R., 1971, Geologic Story of Yellowstone National Park, United States Geological Survey Bulletin 1347.

- Figure 4.7.1: Map adapted by Ryan B. Anderson from: Lund, Karen, Box, S.E., Holm-Denoma, C.S., San Juan, C.A., Blakely, R.J., Saltus, R.W., Anderson, E.D., and DeWitt, E.H., 2015, Basement domain map of the conterminous United States and Alaska: U.S. Geological Survey Data Series 898, 41 p., https://dx.doi.org/10.3133/ds898.

- Figure 4.7.2: Basement Rocks in the Northern Rocky Mountain, Digital Geology of Idaho.

- Figure 4.7.2: Figure 4.6.2: © Ryan B. Anderson. CC BY. adapted from Sloss, L. L., 1963, Sequences in the cratonic interior of North America: Geol Soc. America Bull., v. 74, p. 93-114., and Hendrix, M.S. 2011. Geology Underfoot in Yellowstone Country. Missoula, MT: Mountain Press Publishing Company.